TikTok’s impact on students’ brains

Image used with permission from Google Commons

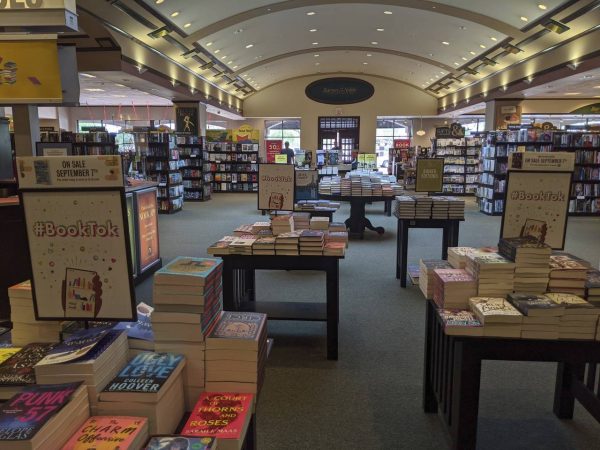

TikTok reached one billion users worldwide in 2021.

In the summer of 2020, I downloaded TikTok. Like other students struggling with pandemic boredom and isolation, I was looking for a way to scroll away my time and connect with kids my age when I had no other way. But just like it did for those others, the app quickly became a much bigger part of my life than I’d ever intended it to – in the worst way possible.

It would be impossible to tell this story properly without first explaining TikTok’s algorithm. On TikTok, the user experience centers around the For You page. When the app is first downloaded, the For You page consists of popular videos of all kinds, i.e. dance videos, comedy videos, cooking videos, etc. As users interact with the app, the algorithm gathers user preference data, so the For You page becomes personalized to one’s interests.

While TikTok has not officially released a description of the app’s algorithm, the basic dimensions it uses to determine a user’s engagement and personalize their feed are obvious: likes, comments, shares and watch times. However, the algorithm most likely uses less obvious dimensions in addition to these, like the “sounds” a user interacts with and the videos liked and engaged with by their followers.

This hyper-specific algorithm is effective in doing what it’s designed to do: keep users watching and engaging with curated content for as long as possible. Unfortunately I, like so many other students, downloaded the app at a time when my mental health was taking a turn for the worse.

Since the emergence of social media, teens have always used it as a platform to vent and relate with one another, discussing topics that, for a long time, were not openly discussed in the public sphere. Before TikTok, there were communities of kids on Tumblr and Instagram that used the sites to connect with others struggling with mental health, oftentimes in harmful ways that romanticized or sensationalized the issues. However, these communities were contained. In order to be fed content like this, users had to search for it through hashtags and usernames, because unless they actively engaged with it, it wouldn’t appear in their feeds or on their explore pages.

The majority of TikTok’s user base is made up of young people, so these communities are still prevalent, but the app’s algorithm doesn’t offer the same kind of shield for young viewers that its predecessors did. Because the algorithm bases user preferences on passive engagement (watch times, “sounds”, and videos their followers engaged with), as well as active engagement (likes, comments, and shares), users are at a much higher risk of being exposed to harmful content just because it uses an audio they’ve engaged with or because people who follow them also watch videos like these.

Pretty much immediately after downloading the app, I started being shown videos like these; Videos lipsyncing to songs about topics like suicide and addiction, usually coupled with text expressing the creator’s depression or nihilism. I never actually went looking for these videos, but as I engaged with them, either actively or passively, they appeared more and more until online school started up again in the fall, at which point they had pretty much taken over my For You page.

With the world still in the throes of a global pandemic, I was now stuck alone in my room seven hours a day, four days a week, and TikTok became my only refuge. The content was seemingly endless and always catered specifically to me. I had an average daily screen time of more than nine hours per day, about 80% of which was spent on the app.

My brain was, as I would later find out, literally addicted to scrolling through videos, depressing or otherwise, and I wasn’t the only one. In April, the Wall Street Journal reported on a study of Chinese college students whose brain scans showed that areas of the brain involved in addiction were highly activated after watching videos on the app.

This is especially concerning to psychologists because the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for impulse control and executive functioning, doesn’t fully develop until the age of 25. This means that teens and young adults on the app are more likely to get addicted to its constant stream of short-term gratification, and prioritize it over activities like schoolwork and self-care, which improve well-being and satisfaction in the long-term.

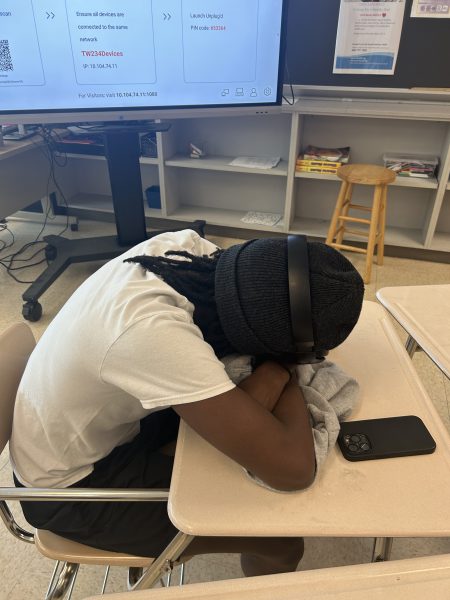

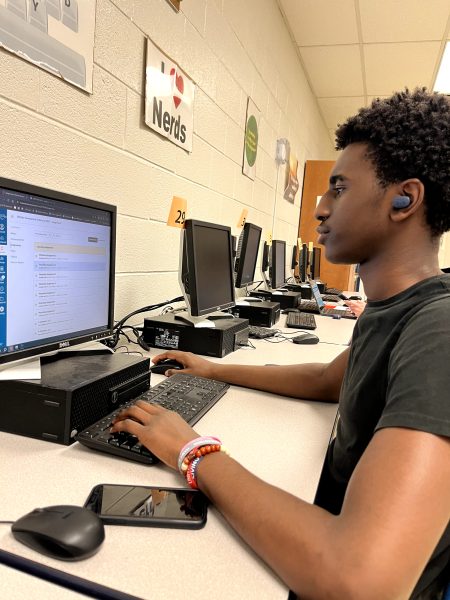

So, I was spending the majority of my days alone, in my room, scrolling through an app that was rapidly deteriorating my already-poor mental health. Before long I had become functionally nocturnal and I was failing in almost every class. Even when I tried to pay attention to my online classes, I couldn’t. I was only ever able to focus on my schoolwork for five to 10 minutes at a time before I got distracted and forgot what I was doing completely. More often than not, I would catch myself mindlessly opening TikTok and scrolling through the first few videos I saw, before trying to regain my focus and repeating the cycle.

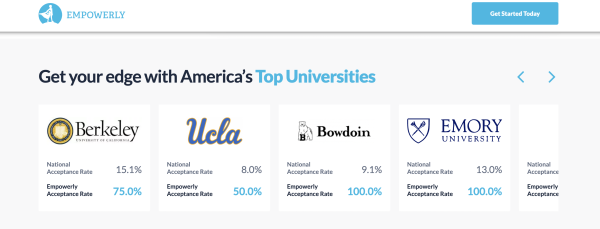

When TikTok hit one billion users worldwide in 2021, I realized that the patterns I had noticed in my experience with the app were likely to be a much bigger issue than I’d initially thought. However, despite the abundance of psychological and neurological research on social media usage in general, TikTok in particular appeared and grew in popularity so recently that I could find barely any research on its psychological impact. Still, research from the few studies I could find confirmed my suspicions.

In a study for the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health that examined a sample of more than 3,000 Chinese high schoolers, researchers found that TikTok usage was consistently linked with depression, anxiety, stress and memory loss.

This is unsurprising, given that social media usage as a whole has been associated with mental health issues in teens. One article for the Mayo Clinic reported that greater social media use in teens, as well as nighttime use and emotional investment in social media, were linked with worse sleep quality and higher levels of anxiety and depression.

TikTok use poses all these same risks, but the app also presents a unique set of issues as a result of its model centering short-form content. The default length of a TikTok video is 15 seconds. While the maximum length was increased to three minutes in 2021, Wired reported in November that the optimal recommended video length (how long a video should be to see the most success) is between 21 and 34 seconds. This element of the platform concerns psychologists because young TikTok users, who make up the majority of the app’s audience, only have to pay attention to content for less than a minute at a time for immediate gratification.

Obviously, it is extremely addictive. Moreover, research has indicated that exposure to digital media in young adults has been associated with long-lasting attention deficits. According to one Harvard study, frequent digital media usage increased the risk of ADHD symptoms in teens by 10%.

Even among students at this school, TikTok has had a significant impact on teens’ attention spans and mental health. Sophomore Sanjana Mudiya said that she’s struggled with these same issues after using the app. “TikTok has such short videos and everything on your For You page is something different, so my attention span has shortened dramatically [as a result of the app,] and gaining so many different pieces of information at the same time has taken a toll on my mental health. My emotions vary depending on the TikTok I watch, so I will immediately go from extreme sadness over a situation, to laughing over a funny video, to feeling pity, and so on. The app doesn’t allow me to feel my emotions to their full extent because they’re just swept away by other short videos,” Mudiya said.

Freshman Vera Shcherbakova described the same experience. “Using social media, especially TikTok, has significantly lowered my attention span and my ability to focus on one topic,” Vera said.

Junior Addy Ziafat described the app using three words: “fun, rotting, addictive.”

Kids on TikTok are increasingly becoming addicted to the immediate gratification the app offers and stunting their brain development in the process, which puts them at risk for attention deficits and mental illness even into adulthood.

Now more than ever, students need to be careful in their approach to social media, but especially TikTok. In small doses, the app may be harmless, but as with anything addictive, scrolling is a slippery slope.

Students: pay attention to what you’re watching, and for how long. When you see content that may be harmful, use the “not interested” feature, and set limits for yourself. On iPhones, you can even use Screen Time settings to limit the time you spend on specific apps.

Even if you continue to spend time scrolling, the most important thing you can do to protect yourself is to train your focus. This means paying attention for longer periods of time to long-form content like novels and films, especially those you can learn from. When you become stuck in a constant cycle of immediate gratification, it’s difficult to pull yourself out, and you may end up damaging your brain more than you ever thought possible.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Thomas S. Wootton High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Senior Isaac Muffett is the opinions editor in his fourth year on the Common Sense staff. When he's not writing or researching, he spends his free time...