Keeping the culture alive: The importance of African American Vernacular English and the significance of code switching

Since its inception, Black people have consistently been at the core of American cultural revolutions and trends. Stemming from fashion and music, to political and social revolutions, Black Americans restructure American culture as we see and consume it. As a result, the epitome of style has and will always stem from Black people and is sourced from everything that is Black culture in the United States, from the clothes they wear, to the way that they talk.

Fashion trends come and go, as we have seen with the repopularization of ‘90s baggy clothes, low rise jeans and crop tops first from the early 2000s. Through the alternations of what is in and what is out, Black slang, acronymed as AAVE (African American Vernacular English), has remained a pinnacle of Black culture. In fact, it has continued to be so popular that it has been adapted by the internet. AAVE has frequently been misconstrued as ‘Internet Slang’ and can be seen often appropriated by non-Black groups that feel as though the adaptation of this vernacular gives them just a touch of the beauty that is being Black. “It is incredibly enraging to see white people who have no business forcing a ‘blaccent’ because it ‘sounds cool’. After the slavery era and segregation, we still face a world where we have had to change the way we talk for years just to be taken seriously while white people try to uphold the way we talk when it has been an utter burden to us for so long,” sophomore Naima Cho-Khaliq said.

While the adaptation of Black vernacular on a wider scope has allowed American society to become more adjusted to AAVE’s existence, that doesn’t mean its acceptance has been anywhere near as widespread. AAVE is simply another variation to the Eurocentric standards inflicted upon Black people, as their existence continues to be isolated and displayed as a perpetual inferiority. Hence, Black slang is often viewed as a social symbol of a lack of intelligence, denoting a perpetually harsh stereotype onto a group that has been victimized for over 500 years. “We have finally found comfort in being OK with the way we talk for moments in a world that would normally point fingers. This assimilation is forced upon us because of the way we are treated when we ‘sound Black’, and it is egregious that we are treated like we’re less educated, of less value, and needed to be attended to in order to function simply because of how we speak,” Cho-Khaliq said.

This discrimination is also psychologically deteriorating, as it requires that Black people must continually alter their comfortability to adjust to the white expectations of social norms.

This transition between using Black slang and actively avoiding it for fear of increased stereotyping has been coined by the term ‘code switching’. Although this term is technically defined as the practice of alternating between languages or varieties of language in conversation, the delineation of Black slang as an official language of its own (AAVE) allows for this term to work in the context of Black-generated language. Whilst AAVE isn’t spoken by all Black people, it is generally accepted as common slang used in largely Black spaces, and is substantially less likely to be heard in spaces that are predominately white.

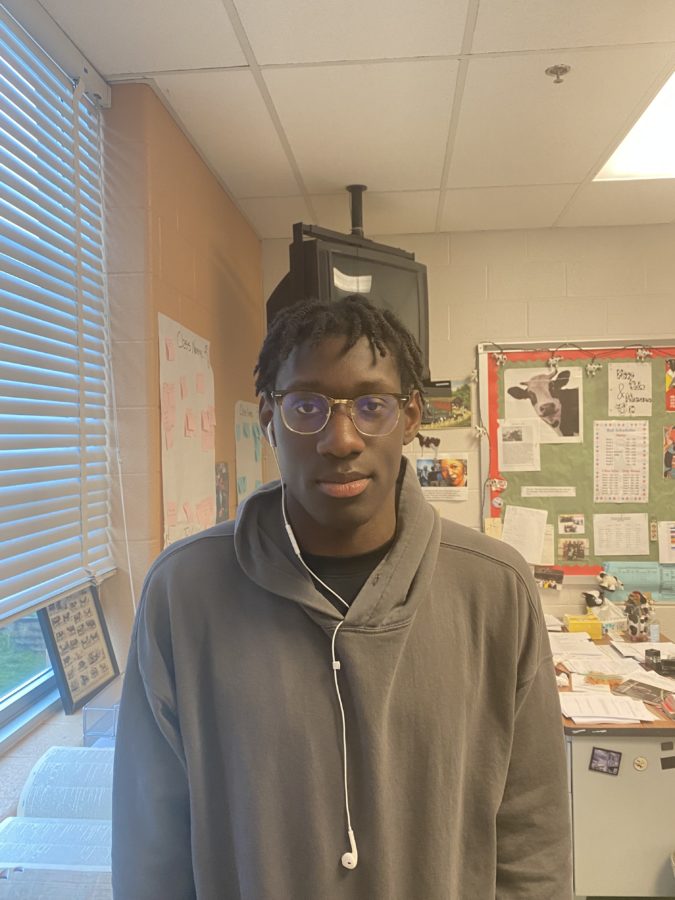

Thus, because many of the spaces at this school are white-dominated, code switching feels like second nature, and has been attributed as a tool for survival and a way to avoid generalizations toward one’s character as a Black person. The switch between AAVE and standard spoken English is used in everyday life, particularly in scenarios where stereotypes can severely impact Black success. “I usually code switch depending on the people I am around. At work, I definitely change how I speak to accommodate white people, people definitely don’t know I’m Black when I am on the phone. Depending on who I’m speaking to, I definitely talk with a more formal vocabulary and I’ve had people ask me if I was the one they were talking to on the phone since they did not expect such a formal voice to come from me,” sophomore Destinee Sousani said.

Code switching, like many other assimilatory activities Black people do on a regular basis, has become an instinctive part of the Black experience that, while it does force us as a group to silence our comfort, has simultaneously showcased the beauty that is embracing what it means to be Black. Black vernacular is worldwide, and its beauty has cemented its place as an integral part of American culture and style.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Thomas S. Wootton High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Margarita is a 2023 graduate.