Instead of solving America’s homelessness problem, hostile architecture is being used to deter the homeless

Photo used with permission from Google Commons

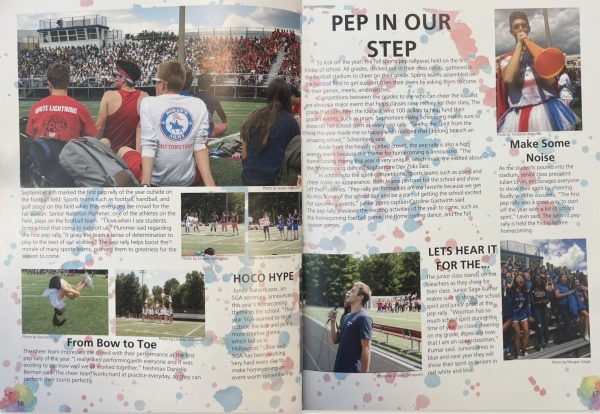

An example of defensive architecture, a bridge underpass is lined with raised bricks in order to deter homeless people from sleeping there.

While walking through the city you may have seen benches separated by metal bars, under-bridge spikes, slanted benches or random spikes and wondered, “Why is that there?”

The term for those seemingly pointless structures is ‘hostile architecture’ — also known as ‘anti-homeless architecture’ or ‘defensive design.’ These terms refer to the infrastructure that city planners purposely build to deter homeless people from setting up camp in public spaces. Anti-homeless architecture manifests in a variety of structures, some common ones being: divided, curved, or slanted benches, spiked window sills, sidewalks and streets, under-bridge boulders and spikes.

In the 2021 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) stated that on a single night in 2021 more than 326,000 people in the United States, 4,430 people in D.C, and 4,048 people in Maryland, experienced sheltered homelessness. The HUD defines sheltered homeless persons as adults, children, and unaccompanied children who, on the night of the count, are living in homeless shelters; that means this statistic does not even begin to indicate the true homeless population since it doesn’t include those who are not able to get a place in a shelter for the night.

According to the website hiddenhostilitydc, defensive design architects claim that these elements are intended to eliminate crime and ensure that public spaces are used for their original purposes. However, this reasoning is just another way of deterring specific, unwanted groups, one of the biggest being the homeless. Another argument made in support of ‘defensive’ architecture, is that by controlling homeless people’s use of public space, it increases perceived safety for others. This in itself is a problematic notion, which uses discriminatory assumptions that homeless people are dangerous.

U.S. Title 42— The Public Health and Welfare states, “the term ‘homeless individual’ means an individual who lacks housing (without regard to whether the individual is a member of a family), including an individual whose primary residence during the night is a supervised public or private facility that provides temporary living accommodations and an individual who is a resident in transitional housing.”

In no part does this definition correspond to homelessness with illegal activity; despite this, due to society’s widespread associations with homelessness and crime, communities have come to demonize the homeless and neglect the United State’s homeless crisis, viewing those without a home as nothing but a nuisance.

Sophomore Nadia Arnold said, “You would think it would be obvious that if we have a large homeless population we should help them and provide housing but I guess it’s not that obvious to the government.”

Anti-homeless architecture is just one piece of evidence of how, in the United States the homeless are treated as pests, eyesores, mere bums… not a problem to be fixed, but one to cover up. Instead, we as a country and a species should be trying to prevent homelessness, and provide shelter and affordable housing options for those who need them, in order to aid against the humanitarian issue that is homelessness.

Nan Roman, the CEO of the National Alliance to End Homelessness said, “I would want (Americans) not to blame homeless people for their homelessness, to understand that the solution is really not that complicated, and to have compassion for people. It seems to me that, in a country as wealthy as ours and as wonderful as ours, we really should not have hundreds of thousands of people living on the street.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Thomas S. Wootton High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.