The filibuster: past, present and future

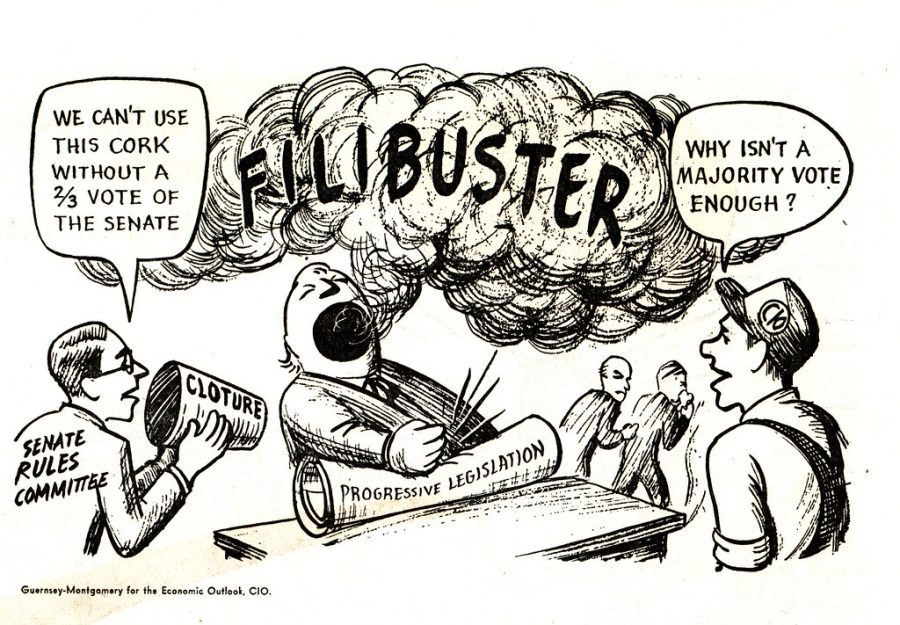

Cartoon by Tobias Higbie used with permission from Google Creative Commons

The filibuster is a senate rule used by the minority to block nearly all legislative priorities.

The Democratic party currently controls the White House, the House of Representatives and the Senate. This “governing trifecta” would seem to allow for an orderly, efficient and robust legislative ability. What stands in the way of the Congressional majority from passing legislation supported by the majority of Americans? The filibuster. In its current form, just 41 senators are empowered to prevent a vote on nearly any bill. There have been exceptions made to the filibuster throughout history, but it remains the obstacle to Congress passing popular policy.

Despite conventional wisdom that our founders intended the Senate to be a slower, deliberative body, the filibuster is not mentioned in the Constitution. According to Brookings, it originated in 1806, when Vice President Aaron Burr recommended that the Senate remove from its rules a provision (formally known as the previous question motion) that allowed a simple majority to force a vote on whatever was being debated.

Filibusters started to be employed during the build up to the Civil War. Leaders from different parties throughout the 1800s would attempt to ban the filibuster. Ironically, these motions would be filibustered by the opposing party. Revisions have been made to the filibuster throughout history, but as it stands today, 60 senators are needed to end debate for the vast majority of issues that come before Congress.

When people think of a filibuster, the image of a senator refusing to yield their speaking time to persuade either the public or their colleagues of their cause comes to mind. This idea is heavily popularized by the movie Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

In practice, modern filibusters are much different. Once debate on a bill has begun, a senator can motion to move to a vote. If there is not “unanimous consent,” another senator files a cloture motion to end debate. If less than 60 senators vote to end debate, a bill has been “filibustered.”

A notable effort to filibuster legislation occurred during the efforts to provide racial justice. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed the House, and would easily have the support of a majority of the Senate. As this vote was pre-1970, when the requirement was lowered to 60 votes, The Civil Rights Act needed 67 senators to cut off debate and allow for a vote.

This sustained opposition to equality came from a group of mostly Southern Democrats and a few Republicans who intended to block a bill supported by the public and large majorities in both houses of Congress. It was framed by President Lyndohn Johnson as a way to honor the slain President John F. Kennedy.

The word “hero” is overused in America, but were it not for the terminally ill Senator Clair Engle, who was wheeled into Congress and pointed at his “eye” symbolizing his vote to end the filibuster, racial justice would have been set back. And as Martin Luther King wrote in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail, “justice delayed is justice denied.”

This Senate rule is currently used as a brick wall to most items of President Joe Biden’s agenda by the Republican minority. The voracious opposition is not new. Shortly after former President Barrack Obama took office, then and current Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell declared that in the midst of a housing market collapse, a health care crisis and double digit unemployment, Republicans’ most important priority was “making Barack Obama a one-term president.”

That refusal to take part in good faith negotiation seems to be repeating itself, with McConnell in the same position. As America attempts to move past a pandemic and restore the economy, McConnell recently proclaimed that “100 percent of my focus is on blocking the Biden agenda.”

The filibuster serves as a cudgel wielded by Senate Republicans to block that Biden agenda, which would, among other things, restore the Voting Rights Act, ban partisan gerrymandering, prevent election subversion, raise taxes on the wealthiest Americans, decrease child poverty and fight climate change.

Due to this intense opposition from Senate Republicans, the only avenue for Democrats to pass significant legislation is an arcane process called budget reconciliation, which is not vulnerable to filibusters. Budget reconciliation is limited to a maximum of three bills per year, but it is often fewer. Thus, most of president Biden’s economic agenda is composed in one bill currently being debated by Congress.

One of the most significant pieces of Democratic legislation, and the most significant health care legislation in recent history, the Affordable Care Act, was passed in 2010 through budget reconciliation. The failed Republican repeal of the Affordable Care Act also utilized budget reconciliation and during the Obama and Biden presidencies, reconciliation has served as the only way to pass large legislation.

The filibuster can often be referred to as a tradition that cannot be changed. This couldn’t be farther from the truth. Not only did America begin without a filibuster, the amount of votes required to break a filibuster has been reduced over time, as well as what a filibuster can be used for.

It can no longer be used to block presidential appointments to the Cabinet, as well as for federal and Supreme Court confirmations. Recently, there has been debate over an exception for the filibuster to prevent government shutdowns and Democratic activists have pushed for a voting rights exception to the filibuster in the face of a wave of voter legislation.

The advocates of the filibuster proclaim that a requirement of 60 senators to pass legislation fosters bipartisanship, and prevents the tyranny of the majority. With regard to bipartisanship, it does the opposite. It allows a minority of just 41 senators to reject any attempts at bipartisanship. If there were no filibuster, the minority would be incentivized to engage in bipartisanship, due to the likelihood of legislation passing regardless of their view.

It is extremely unlikely that the filibuster would be abolished. West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin and Arizona Senator Krystem Sinema have repeatedly defended the filibuster and seem unwilling to repeal it. In the minds of other Democrats, they have prioritized procedure over people.

Republicans across the country have passed legislation that removes ballot drop boxes, decreases polling places and restricts early voting. Additionally, they have empowered partisan state legislators to overturn elections certified by nonpartisan election officials. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, 18 states have passed 30 laws designed to make voting more difficult. The compromise voting rights legislation, The Freedom to Vote Act, protects the right to vote and would work to prevent election subversion. Republicans filibustered an earlier version of this legislation, and seem set to do so again. The Voting Rights Advancement Act, which would prevent similar laws from being passed without Justice Department approval, has the support of just one Republican senator, Alaskan Lisa Murkowski.

2018 Georgia gubernatorial candidate and voting rights activist Stacey Abrams has advocated for a voting rights exception to the filibuster, saying that “Democrats should take bold action to protect our democracy” due to the voter suppression legislation, and her view holds that “Eliminating voter access under the guise of race-neutral actions that clearly target communities of color is nothing short of Jim Crow 2.0.”

Filibuster reform seems to be the more likely option. There are several proposals. Among them, a filibuster that has a time limit, in which the number of senators required to break a filibuster decreases over the period of a few months until a simple majority can call a vote. Additionally, the numbers of sustaining a filibuster could flip. This would mean there need to be 41 senators in the chamber, maintaining the filibuster at all times and a vote can be called once that number dips below 41. All of these proposals would allow the majority the ability to govern,

and provide the minority ample time to voice their concerns, while preventing them from becoming obstructionist

The instinct to blame both parties for partisan gridlock is a powerful one. However, in the face of a pandemic last year, nearly every Democrat voted for economic relief legislation, even if it could have hurt them politically. Nearly a year later, just emerging from a brutal pandemic winter, not a single Republican voted for the American Rescue Plan, a piece of legislation supported by a plurality of Republicans, and over 70% of Americans, according to Quinnpiac.

Perhaps the most statistically significant use of the filibuster in opposition to broadly supported legislation came when bipartisan gun control sponsored by West Virginia Democrat Joe Manchin and Pennsylvania Republican Pat Toomey failed in the Senate despite the support of 54 senators.

Multiple surveys by Suffolk university, Harvard University and Pew Research showed over 90% nationwide approval for increased background checks and other measures in that legislation. The unanimity of the American public was no match for the filibuster, as that legislation died in the Senate.

Presently, the voting and election subversion legislation passed by Republicans juxtaposed with legislation designed to make it easier to vote, such as the Freedom to Vote Act and legislation like the John Lewis Voting rights Advancement Act present a clear choice for Democrats: democracy or the filibuster.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Thomas S. Wootton High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Ethan is a 2023 graduate.