The criminal justice system in the United States has long been the subject of accusations of bias in its workings, most notably racial bias.

According to Radley Balko of The New York Times,“the evidence of racial bias in the criminal-justice system isn’t just convincing — it’s overwhelming,” listing a large group of studies and data to support his argument. According to the studies that Balko mentions, African-Americans and Latinos are more likely to be arrested, pulled over, or suspected of crimes regardless of the percentage of the population they make up.

Balko reported that “A 2017 report by the Sarasota Herald-Tribune of Florida’s drug convictions found that while blacks made up 17 percent of the state’s population, they made up 46 percent of felony drug convictions since 2004. In all, when blacks and whites committed similar drug crimes, blacks on average received a sentence that was two-thirds longer. In some parts of the state, it was two or three times longer.”

Other studies listed in the article argued that this difference in the justice system is large enough that it could not be considered natural. Balko cited “A 2011 study from Michigan State University College of Law [which] found that between 1990 and 2010, state prosecutors struck about 53 percent of black people eligible for juries in criminal cases, vs. about 26 percent of white people. The study’s authors concluded that the chance of this occurring in a race-neutral process was less than 1 in 10 trillion.”

According to an article by Leah Sakala and Nicole D. Porter, the reason for this proposed partiality “is that implicit bias and structural racism ensnare people of color — particularly black, Latino and Native American people — in the justice system at astronomical levels, and the evidence is clear that people with identical criminal histories who have committed the same crimes are nonetheless treated differently because of the color of their skin.”

The article argues that this implicit bias is deeply rooted in the US justice system, and advocates for long-term, wide-ranging operations to change the system.

On the other side of the argument, P.A. Langan of the National Criminal Justice Reference Service stated that while a great many studies provide evidence for bias, many of them have not, and the evidence of bias is weak at best. According to Langan, “Compared to legitimate factors affecting sentencing decisions, such as the defendant’s prior record and offense seriousness, race appears to be only weakly related to whether a defendant is arrested, convicted, prosecuted, or sentenced severely.”

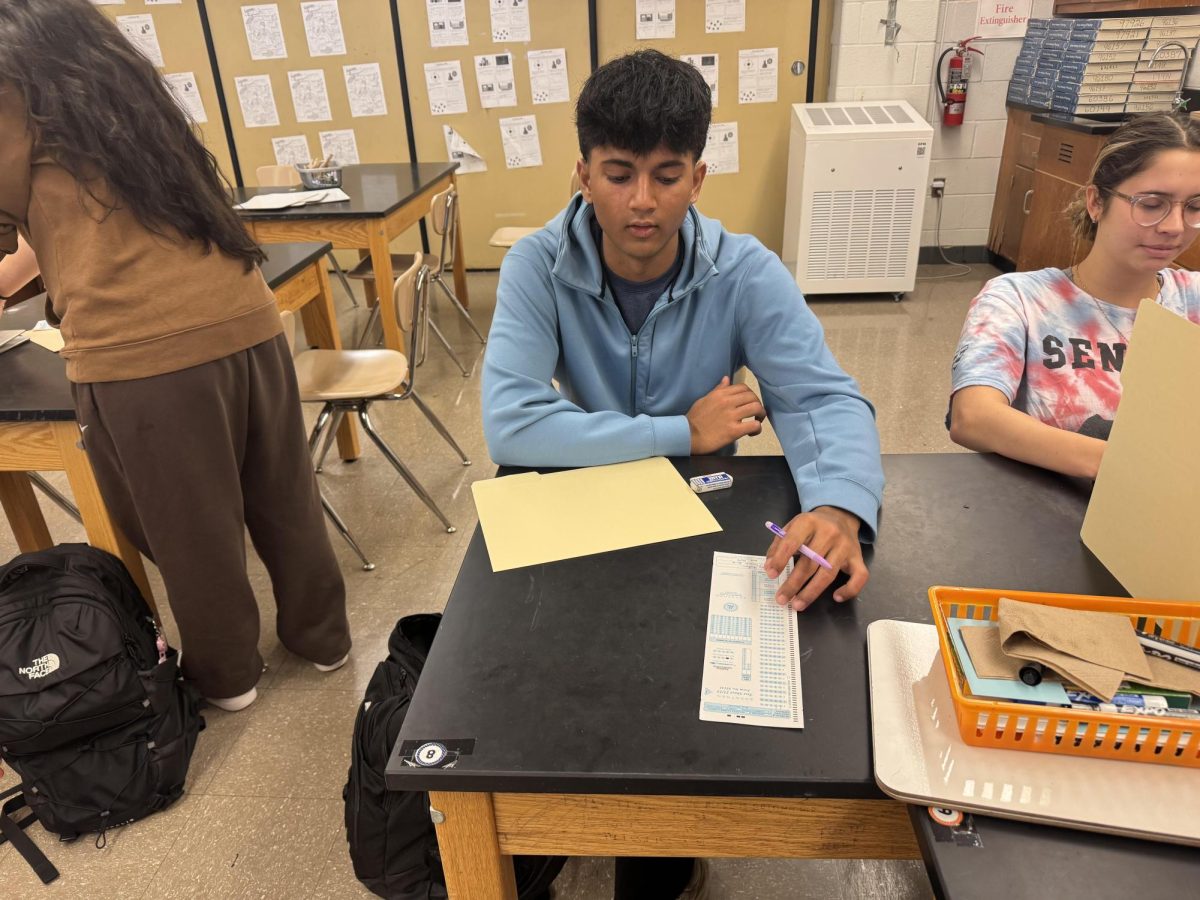

Students have mixed opinions on the controversial topic. “I think overall [the justice system] does its job. Could be a better though,” Sophomore Joaquin Moreno said.

AP Government teacher Christopher McTamany said that the subject of biases in the justice system is not a subject often studied in high school. “You might see it in an AP government class [but] it’s not a specific thing that’s part of the AP curriculum,” McTamany said.