John Riker

editor-in-chief

Defend your home turf!

For students at this school, home turf constitutes a long, meandering and often confusing strip of Montgomery County estate. The cluster stretches from the riverside Tobytown community to the west, to the RIO Washingtonian Center to the east and is sandwiched between the Dufief community to the north and Cold Spring to the south. Soon, another adjective will be added to the list of descriptors of this school’s home turf – contentious.

On Sept 24, the MCPS Board of Education ruled 5-3 to use diversity as the most important consideration when drawing school boundaries. The decision was fueled by the desire to close the achievement gap within the county’s school system and boost racial and economic inequality. According to MCPS officials, the new boundaries will not affect the school assignments of current students and younger students could be grandfathered in. While this ruling does not change any current school boundaries, the policy will literally shape our county in the coming decade when the planned Crown High School opens as well as provides insight into one of the most important educational issues in our school system.

Achievement Gap and Diversity

Though Montgomery County is one of the most diverse areas in the United States, the demographic breakdowns of high schools fail to reflect it. According to 2017-18 data released by MCPS, 160,073 students attend MCPS schools, with the Latino demographic leading the way with 30.8 percent of the population, followed by white (28.3 percent), black (21.4 percent) and Asian (14.4 percent). But among the district’s 25 high schools, the demographics differ greatly. This school’s population is only 7.7 percent Latino (tied for lowest in MCPS) and 6.4 percent black (23rd in MCPS), while the school has the highest percentage of Asian students of any MCPS school with 37.1 percent, and is 44.2 percent white. Contrast those statistics against our neighbor across the 270, Gaithersburg, which is 50.1 percent Latino and 23.9 percent black.

The numbers are especially problematic when it comes to economic inequality. This school, along with Whitman and Churchill, are the only three high schools in the county with five percent or less of its population qualifying for Free and Reduced Meals (FARM). The FARM rate rises substantially when looking at schools across the 270 highway, with Gaithersburg at 40.1 percent and two other schools above 50 percent The disparity is at its highest in elementary school, where nine schools have FARM rates above 80 percent while three elementary schools within our school’s boundaries are below 7.5 percent.

These differences in race and class have correlated with performance in the classroom. Six of the county’s high schools graduated 95 percent or more of their senior class in 2017-18; all six schools drew the majority of their students from west of the 270 (the seventh, B-CC, missed by 0.6 percent). Though two of the major high school magnets (Richard Montgomery and Blair) are located on the east side, students on the eastern side do not benefit from multiple programs instilled in their higher-income counterparts. From this disparity,the “W” schools west of the 270 (Walter Johnson, Whitman, Wootton, Winston Churchill) have established strong reputations, while an achievement gap has formed between them and other MCPS schools.

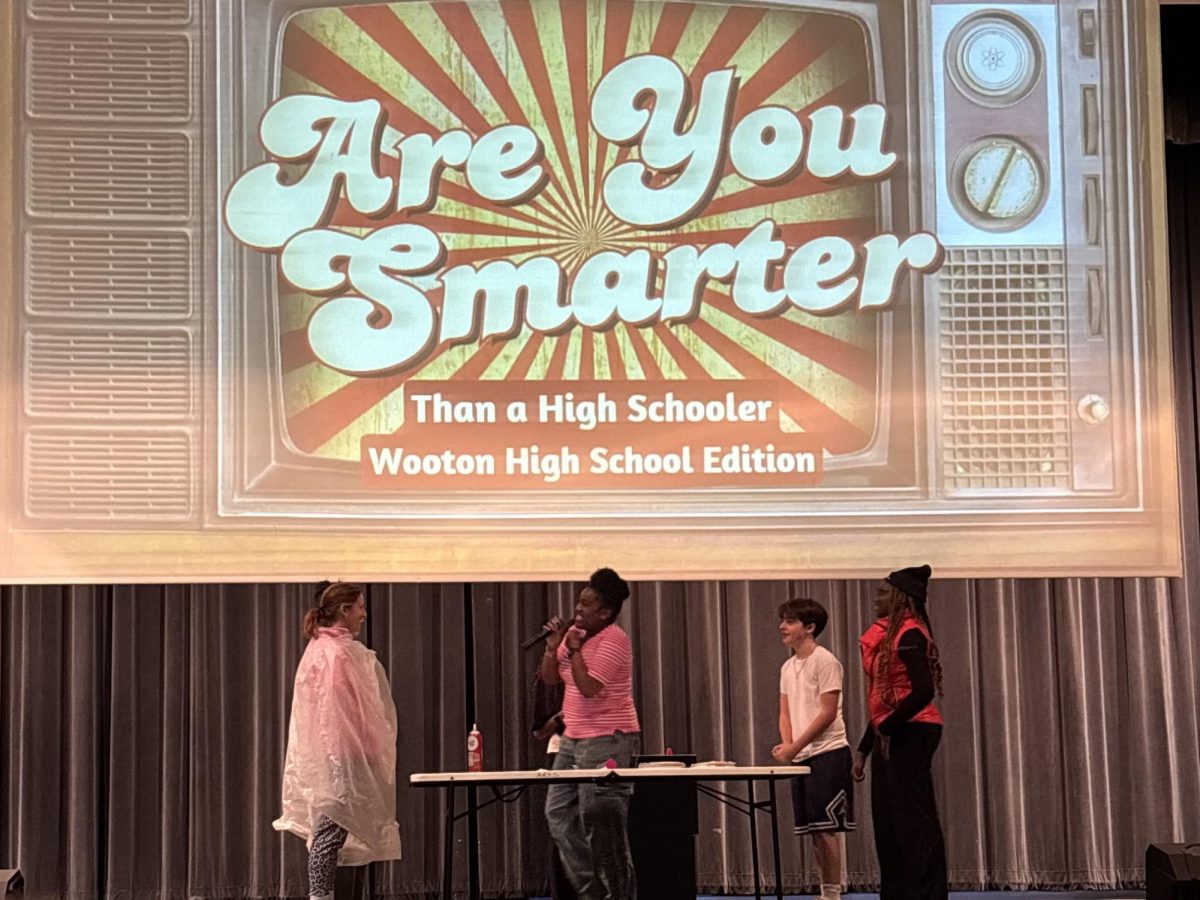

Senior Dajah Lockett, President of the Minority Scholars Program, views the achievement gap as a pressing issue. “If the goal of Wootton and most high schools is to have everyone graduate and make a life for themselves and be successful, then you can’t really have the achievement gap,” Lockett said. “The achievement gap is what leads to the lack of success, and when there is the lack of success there will be the continued cycle of certain groups of people being ones that fail. And we can’t have this thriving economy that everyone talks about when there’s still this large section of the community constantly failing and being put on the side.”

Closing this achievement gap is easier said than done. In the past few decades, each MCPS superintendent has prioritized the problem, yet the gap has grown wider than ever. MCPS can’t simply redraw the boundaries, either.

“We need to strengthen all schools so they all appear to be desirable so it wouldn’t be as big of an issue,” County Board of Education candidate Brenda Wolff said at a forum on Oct 10, as reported by Bethesda Magazine. “People have these perceptions about schools and we need to change those perceptions.”

Enter the recent school boundary policy. Current MCPS Superintendent Jack Smith’s proposal for renovation and expansion of schools, which included the 2022 construction of Woodward High School in Rockville and the future construction of a high school next to the Downtown Crown and RIO shopping centers, opened a door for MCPS to tackle the achievement gap in setting the boundaries for the new schools. Woodward will pull from the Whitman, Walter Johnson and B-CC schools as well as some from the Downcounty Consortium, while Crown figures to combine students from Gaithersburg, Quince Orchard, Richard Montgomery and this school. The clusters feeding into those two schools have a wide demographic, but while the new boundaries are a prime opportunity to address the achievement gap, the road ahead is difficult.

Contested Change

The policy changing how school borders are created may have changed, but the futures of the school boundaries of Woodward and Crown figure to be heated battles. Due to the reputations of the “W” schools, parents of students have strategically bought houses or apartments to ensure that their child could attend one of the higher-income schools. There are even students who live in other school clusters but own property in this school’s district and choose to make the long commute, in the name of what they perceive to be a stronger education.

Prior to entering high school, senior Jason Li moved into an apartment at RIO, just on the border of this school’s cluster. Enrolling at a school with a strong reputation was his top priority.

“Wootton has this reputation for being a really good school, so when people buy houses or rent houses, it’s what they take into consideration,” Li said.

Crown’s boundary would affect students living in the RIO area and likely other neighborhoods that currently feed into this school. The DuFief neighborhoods along Darnestown Road are also a possibility to be assigned to Crown, a move which could frustrate parents who intended to live in this school’s cluster. Transportation and proximity to assigned high schools are additional challenges that must be addressed when drawing boundaries.

On the flipside, homeowners in our school district in the homes that stay within our school’s boundaries could see drops in the value of their homes when the new boundaries are drawn. A central attraction of homes in this school’s cluster is the high performance and reputation of the school, and by redrawing boundaries to include more lower-income communities, the financial value of being in the cluster could diminish. A portion of these homeowners have expressed support of efforts to close the achievement gap, but do not believe that using the already contentious issue of school boundaries is an adequate solution and are frustrated that their position is portrayed as opposing diversity.

There’s also the question of whether changing the school boundaries would be an effective measure, and funneling all efforts for racial and economic equality into solely this new policy could be a recipe for disaster. The school boundary policy will come into play when Woodward and Crown are constructed, which targets areas in Rockville and Gaithersburg where there are significant divides, but in those cases it only affects the schools in those areas, while the majority of high schools are not addressed. Plus, the borders of schools can only impact the school to a limited degree as most of the school cluster would stay intact. Internal changes, such as initiatives for students to be involved in honors and AP courses and support for students in lower-level classes, could provide a more effective and direct way to attack the achievement gap than one widespread measure. Given the significant time and financial demands that a policy like the boundary measure will require, the Board of Education would be wise to consider multiple potential avenues of closing the gap and listen to the input of the community before taking action.

Valuing Diversity

Whether or not the initiative for diversity succeeds, the policy sends a clear message that MCPS needed to get across – the achievement gap is a problem that MCPS is committed to resolving. And if the new boundaries help the county make tangible strides in closing the gap, the effects of a more equal educational experience would make a significant difference.

“I think [the policy will be successful] because, again, the whole aspect of diversity is another thing that plays into the achievement gap,” Lockett said. “A part of the achievement gap is going into a classroom and seeing nobody who looks like you, as a minority. When you’re able to bring more minorities into the classroom, that brings the sense of “I can do this.” And then you’re more likely to succeed because there’s that common ground in the class.”