There was a time when asking a teacher for a college recommendation letter came with butterflies in your stomach and a thank-you note in your hand. Maybe even a little bag of chocolates or a gift card — not because you had to, but because you wanted to. You knew it was a big ask: You understood they were going out of their way, unpaid and outside of class hours, to write a letter that could open doors for you.

But something has shifted.

These days, recommendations are just another checkbox filled with pressure, as if it’s part of the teacher’s job description to drop everything and play a supporting role in your college dreams. And while the demand for these letters has skyrocketed, the empathy from students has bottomed out.

In response, teachers have begun closing gates, limiting the number of letters they’ll write; saying “no” more often. Not because they don’t care, but because they’re tired of feeling like a vending machine for Ivy League praise. What happens when respect goes missing from something so deeply personal? What do we lose when the letter of recommendation, a once sacred tribute, starts to feel like a factory product?

According to Sara Harberson, large public universities are starting to end the requirement for letters altogether. Even selective schools like New York University and Tufts have cut down to only one required letter. With these schools receiving hundreds of thousands of applications each year, it makes sense, but it’s also reshaping how students approach the process. Teachers are getting fewer asks. Students are becoming more strategic. And the moment of choosing someone who really knows you is starting to feel like a transaction rather than a thank you.

Even though recommendations are still supposed to come from teachers who know you the best, asking isn’t what it used to be. There’s a performance in the way we do it now; it’s a quiet calculation. We ask ourselves: What will make them say yes? Will they remember me? “I think everybody tends to put on a slightly nicer persona. For me, it’s because I can’t remember what their last perception was of me. So I want to change it up just a little bit,” junior Amal Shaikh said.

For senior Manny Perez, the pressure to perform wasn’t as intense. His asks were casual by design. “As long as you choose the teacher you really resonated with, then you’re gonna be alright. None of [the teachers who wrote my recommendations] specifically had any rules, they just told me to ‘ask after APs.’ It didn’t feel like bothering them, as long as we just asked after APs,” Perez said.

Still, even for Perez, the pressure around timing crept in. “There was definitely pressure [to ask], because everyone was asking their teachers and saying you had to ask at a specific time, but really it was dependent on when the teachers wanted you to ask, honestly. I don’t think I would do anything differently with my recommendations,” Perez said.

For Shaikh, the pressure to move fast was all-consuming. “I’ve already asked for both of my letters of recommendation because I was advised by my counselor to ask before spring break,” Shaikh said.

To make things easier on herself, and her recommenders, Shaikh built out a brag sheet. “I 100% believe it’s easier for the both of us. Again, I don’t know if they remember who I am at all as a person, so having it all written out for them is very beneficial for the both of us,” Shaikh said.

The line between strategy and sincerity has blurred, and teachers are feeling it too.

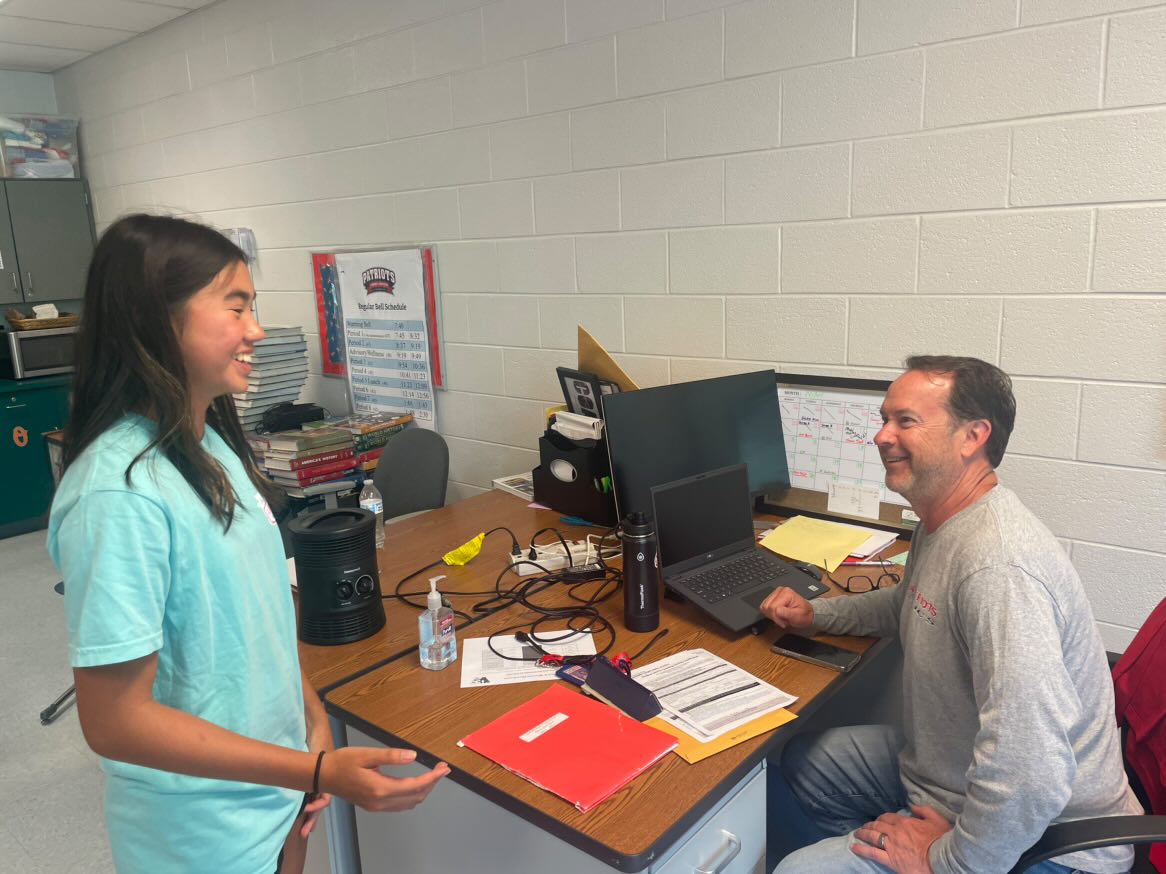

Spending one week in English teacher Melanie Moomau’s class, you’ll know her boundaries are clear. She caps her letters at 20 a year, which, compared to other English teachers, is seemingly generous. Celebrating students matters to her, but so does protecting her summer, which she cannot do if she’s being overworked. With all these factors combined, it is still set in stone that you must earn a letter of recommendation from Moomau. “I say yes to people who are active members of my class. It’s not about grades, but about academic honesty and class presence. If someone plagiarized, I will not write a letter for them. If someone sits silently in my class, even if they have a decent grade, I will often say no to a letter of rec,” Moomau said.

English teacher Daniel Pecoraro’s mindset is much more open. “I think not a lot of students have a teacher whom they can trust and feel comfortable asking. I want to be the teacher for the kids who might not be the most academic and high-achieving, so I want to be open to all types of students. I try to imagine the student as I’m writing the letter, and I try to focus on their best moments, focusing on the growth I did see. I treat each letter as a reflection of each student,” Pecoraro said.

Neither stance is wrong, but their limits reflect a change in how we value teachers’ time.

More students are applying to more colleges than ever before, applying to 10, 15, even 20 schools. And while certain colleges are easing their rec letter requirements, others are doubling down, asking for two instead of one. Students are stuck in a loop: feeling guilty, feeling entitled and most of all, feeling the pressure to perform. The Common App reports that the average number of applications per student has seen a 4% increase, and the National Association for College Admission Counselors has similarly noted a 6% increase in applications from first-time freshmen. This growth in applications puts additional strain on teachers, who are now expected to push out more recommendation letters, and often under tighter deadlines as well.

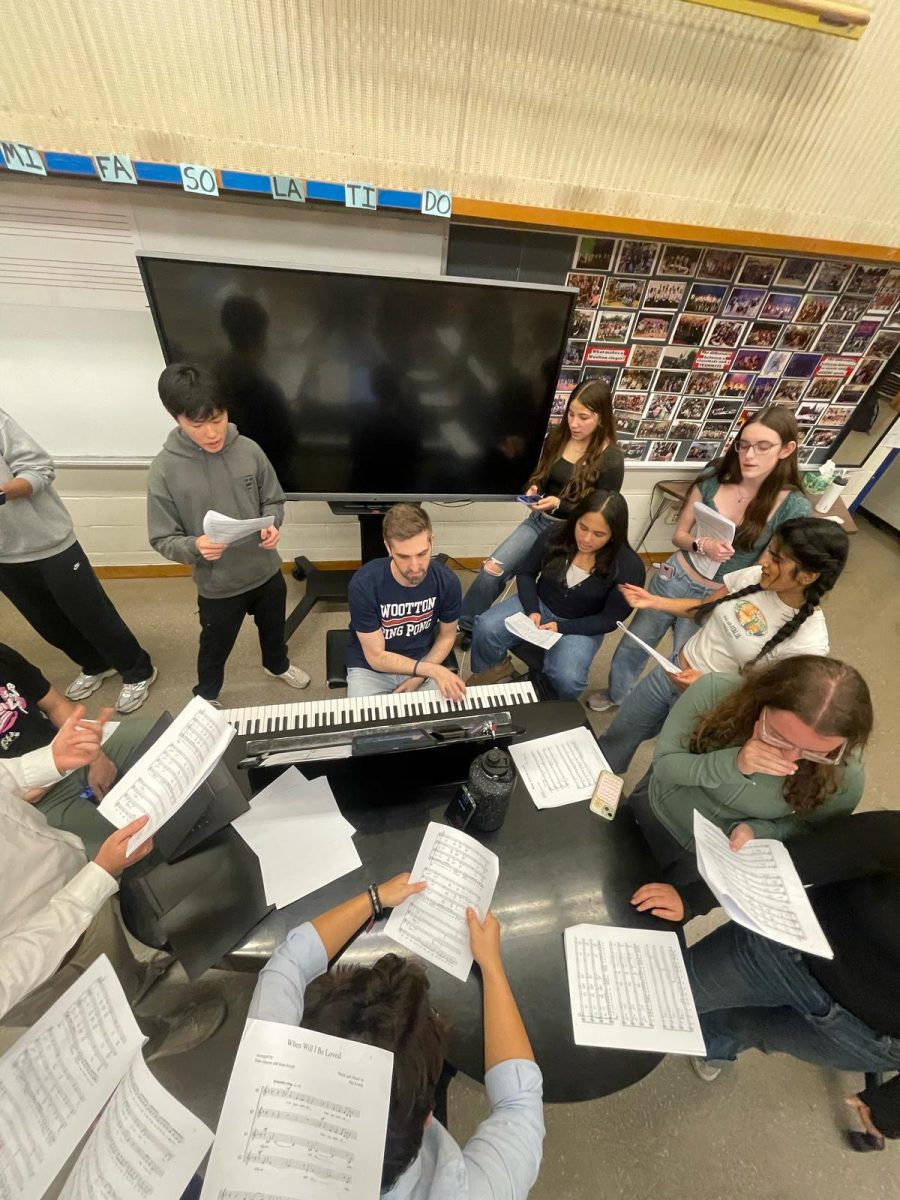

The personal stories that don’t fit a brag sheet are often the ones that matter the most, but if your teacher doesn’t know them, they can’t write them. There is an emotional weight to a teacher writing, “I will never forget this student,” and that should mean something. When teachers are presented with the option of writing for a student they barely knew — or worse, don’t remember — it starts to feel empty. The tradition of trust between a student and a teacher that once defined this ritual is starting to fade, and it’s something that cannot be replicated. Can something feel meaningful when it’s expected from everyone? “Every year when I give my seniors their gifts, I handwrite a long note for each of them — that feels more personal and meaningful than a recommendation letter, which says a lot,” chorus teacher Keith Schwartz said.

The letter of recommendation feels like a factory product for those involved – teachers and students. Students are losing their willingness to ask teachers they felt personally connected to for recommendations, in exchange for letters from teachers whom they only see in academic settings. The teachers who do form personal connections are writing fewer and fewer letters, and, while everyone complains about the birth spike beginning to hit colleges, it seems that the loss of respect has also begun hitting, and it’s only growing.

The only way this problem can be solved is to start appreciating those who have stood up for us no matter what: teachers. We need to stop treating them like a means to an end. We need to start showing up with thank-you notes, not just request emails. We need to bring back the butterflies, the awkward ask, the eye contact, the humanity. Because if we keep running this whole process like a cold, strategic exchange, we’re going to forget the people who helped us get here in the first place. And maybe worse: they’ll forget us too.