“As you arrive, through a small gate in the trunk, you find yourselves staring into the far end of a great arena built into the tree. You can hear the cheering of hundreds of elves and thousands of woodland creatures come to watch your trial. The Cnhamnians have welcomed you into their coliseum to test you as they would test their own finest soldiers, it seems. Yet, while the majesty of it all enshrouds you, there is a steady worry in your hearts, a sense of danger that you have only felt before in the eyes of your most treacherous enemies. The crowd roars even louder, chanting a phrase you can’t quite make out in a language you don’t quite recognize. And as they cheer, as if summoning your opponent, the bark of the Great Elm at the far end of the stadium unfolds. Then, as if growing from the tree itself, Autumn, the Lichbeast of Leamhan, is before you. She waits a mere hundred paces forth, patiently gazing upon you with her emerald eyes. She roars, a sound like a thunderstorm echoing through a hollow log, and beckons you to contest.”

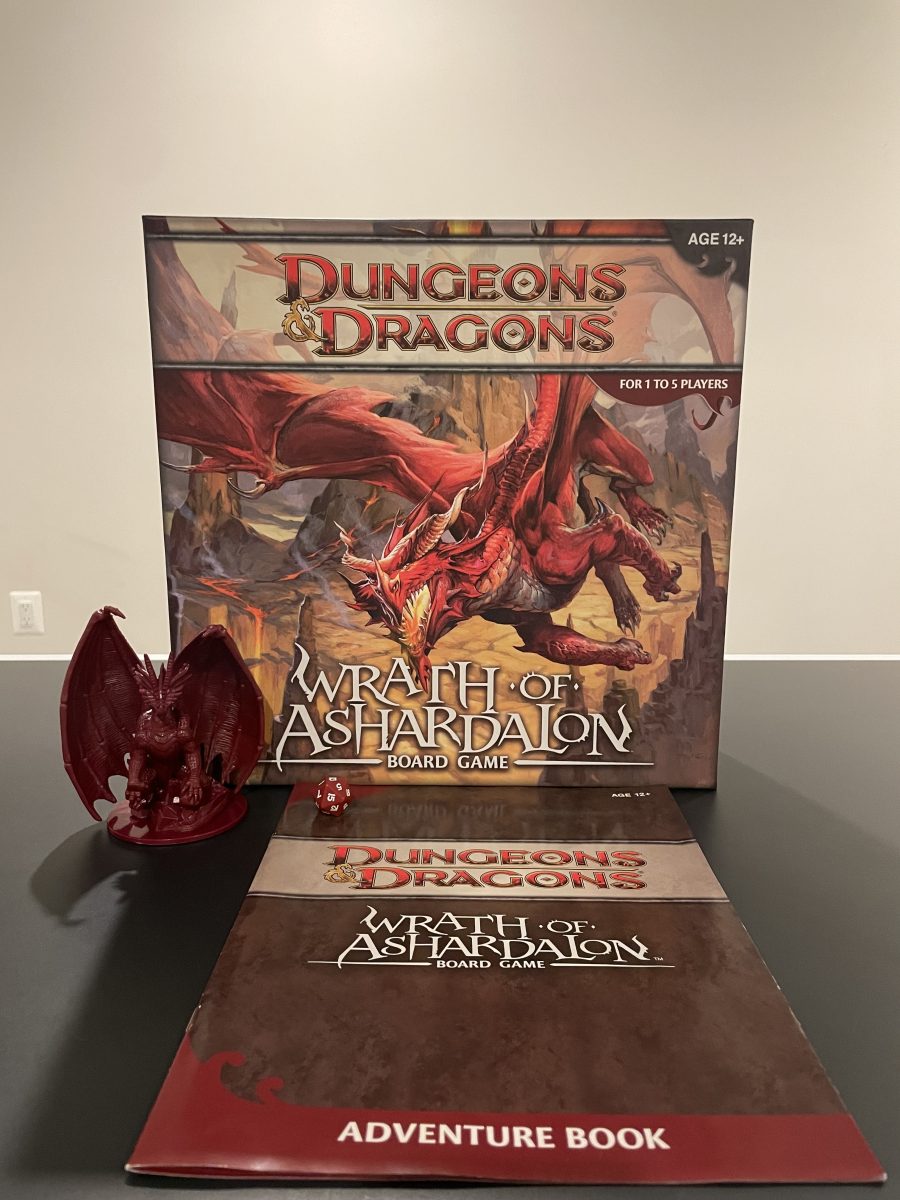

That was an excerpt from the story of A Song of Storm & Stone, a Dungeons & Dragons campaign being run by senior Terra Muffett. Muffett has created an entire fantasy world for the members of the Tabletop Gaming Club (or DND Club, for short) to immerse themselves in: a world rich with history and lore, a world filled with monsters and magic (and even a few guns!), a world where elven nobility and writhing hell-beasts fight together as allies, and most importantly, a world where the decisions made by the players will permanently alter the story. And the most fascinating part?

All of this is standard for this club. A Dungeon Master is not simply a narrator – they are an artist, a poet, a rhapsode, someone who creates a living, breathing world populated by living, breathing people that changes according to the whims of both its author and its audience.

I myself am not a Dungeon Master; I am merely a player – the “writhing hell-beast” mentioned above, in fact – and my own words cannot do the art of DMing justice. Instead, I will relay the words of the people behind the magic: The Dungeon Masters of the DND Club.

Just as novelists have their own “voice” that is unique to their writing, every Dungeon Master has their own “style” and no two DMs will run a campaign in the same way. However, DMs can still be broadly categorized by how they prefer to play the game. Muffett outlines a few of these categories, saying that some DMs are “railroad-y” and will “push their players to a very specific path” and “want their players to follow through a specific story,” while others are “crunchy DMs,” who prefer “doing stuff that requires a bunch of math and a bunch of calculations” and encourage metagaming. Muffett puts herself into the “roleplay” category of DMs, putting a heavy focus on creating a “character-driven” story that gives the players a lot of freedom. She said that, in her campaigns, “the story comes first.”

Anthony Shadman, the sponsor of the DND Club, described his own style similarly, saying that he is “more storytelling heavy” while trying to “keep things flexible and creative.” Shadman also said that he avoids using sourcebooks and prefers homebrew, saying that it allows his games to “be more reflective of the players and what they’re looking for in an adventure.”

It is clear that, to the DMs of the DND Club, the players are of the utmost importance. Both Muffett and Shadman enjoy one thing above all else when DMing: seeing the reactions of the players. Muffett said that she enjoyed “the face that players get when they solve a puzzle,” or “when a player picks up something that sort of ties their whole character together.” In Shadman’s words, DMs enjoy seeing players have their “a-ha moments.”

However, even if a Dungeon Master is able to accomplish all of these things, it won’t matter if their campaigns aren’t fun. Fortunately, there’s no shortage of entertainment within the campaigns of the DND Club. One of Muffett’s campaigns contains the story of Eilorf, a character Muffett describes as a “small little halfling boy.” For context, within the campaign, a close friend of Muffett, Leo, was playing a character named Mordecai, who “had voices in his head.” Every time those voices spoke, Muffett would require the player to roll a Wisdom saving throw in order to “resist” those voices — essentially, Leo would have to roll a 20-sided die to not listen to the devil on his shoulder, and if he rolled too low, then bad things happened. It just so happened that at one point, Eilorf was dangerously low on health in a fight, and as Mordecai came over to support him, Muffett had the voices in his head tell him to, quote, “Punt the child.” So, Leo performed his Wisdom save, and rolled a 1. Muffett then had Leo roll Strength to determine how hard the child would be punted — and Leo rolled a 20. Muffett said, “I described, in detail, him kicking Eilorf so hard he cracked through the magical barrier they were trapped in and got sent into the sun and went through the Seven [sic] Hells and met a couple Gods on his way down.”

Dungeons & Dragons is a wondrous experience, and none of it — the fantasy, the roleplay, even the child-punting — would be possible without the work of the Dungeon Masters.

![Editors-in-Chief Ahmed Ibrahim, Helen Manolis, Cameron Cowen, Alex Grainger, Emory Scofield, Hayley Gottesman, Rebekah Buchman and Marley Hoffman create the first print magazine of the year during the October press days. “Only a quarter of the schools in MCPS have programs that are like ours, a thriving, robust program. That makes me really sad. This is not just good for [the student journalists] to be doing this, it’s good for the entire community. What [student journalists] provide to the community is a faith in journalism and that continues for their lifetimes," Starr said.](https://woottoncommonsense.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/wmpoFTZkCPiVA3YXA4tnGoSsZ4KmnKYBIfr18p3l-900x1200.jpg)