I’ve never been one to shy away from a challenge. Over the years, I’ve thrown myself into just about every sport you can imagine— downhill skiing, basketball, football, skimboarding, and at the very top of my list, soccer. Through all those experiences, I’ve racked up more than just memories. I’ve collected a long list of injuries: a broken leg, a fractured arm, a dislocated collarbone, not to mention countless bruises and stitches. It’s part of the game, but at what cost?

For the past four years, I’ve proudly worn a jersey for our soccer program. But if you look at the stat sheet, you might wonder where I’ve been all this time. Despite my dedication and practice, I’ve spent less than half of my high school soccer career on the field, sidelined by injury after injury. Yet, nothing prepared me for what happened on Oct. 2.

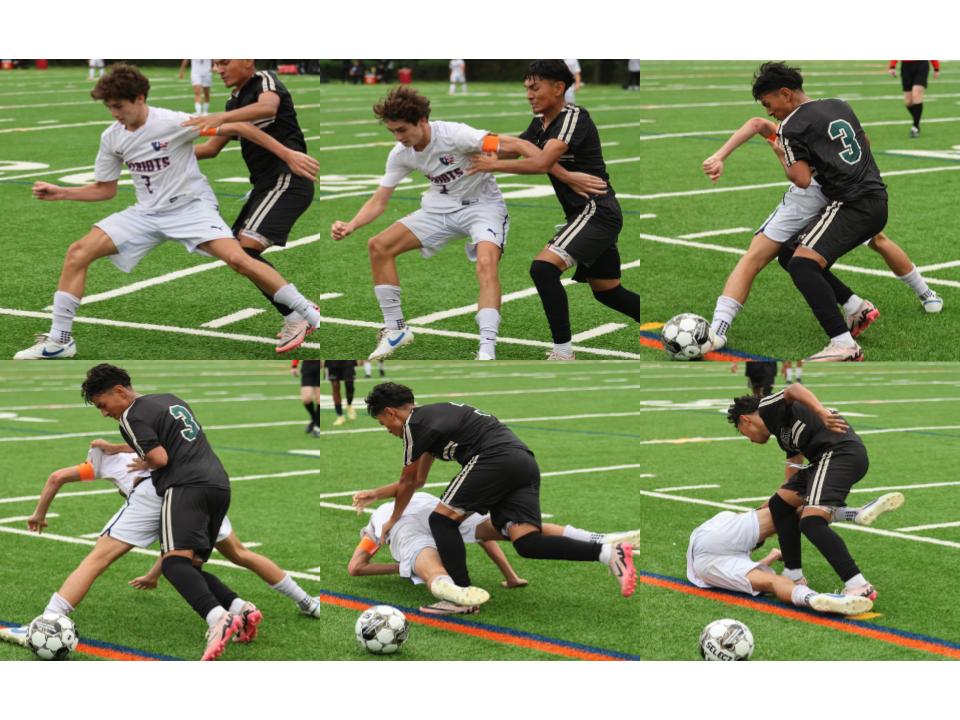

It was a typical high school soccer match — physical, aggressive, and fueled by passion. We were playing against John F. Kennedy, and with 20 minutes left, we were down by a single goal. That’s when it happened.

A teammate flicked the ball forward, sending it into open space for me to chase. Ahead of me, I saw an opposing defender in pursuit. He wasn’t backing down, and neither was I. Either he hits me or I hit him. I braced myself and charged, but as we both rose to contest the ball, I miscalculated, and we collided — head to head, skull to skull.

The impact was immediate. I hit the ground hard, my ears ringing like a gunshot had gone off beside me. Dazed and confused, I stood up, but the world spun around me. The crowd roared, and players surrounded me, but it all felt distant, like I was floating somewhere else.

Suddenly, I was surrounded — teammates, coaches, the trainer. I could barely process what had happened before the trainer started asking me questions. “Recite the months of the year backward,” she said. “What’s your name? Where are you right now?”

It felt surreal, like I was being quizzed on random facts while my head was still spinning from the impact. The whole assessment took maybe five minutes. Given my history — this being my second concussion — I knew something wasn’t right.

But to my shock, I was cleared: Cleared, even though I was disoriented, nauseous and unbalanced. No concussion, but as a precaution, I wasn’t allowed to return for the remainder of the game. It wasn’t until I saw a specialist days later that I got the official diagnosis: a concussion.

Looking back now, the experience hasn’t just changed the way I think about my playing style — it’s changed the way I view sports medicine, especially when it comes to concussions. Trainers and medical staff need to do more than just rely on basic protocols or five-minute assessments. Athletes deserve better care, especially when dealing with injuries that aren’t immediately visible. A head injury isn’t something to brush off, and the current systems in place for concussion protocol often fall short of protecting players in the long run.

Currently, Montgomery County Public Schools (MCPS) follows a structured six-day return-to-play protocol for student athletes recovering from a concussion. The process begins with the athlete being symptom-free for 24 hours before starting light aerobic activity like riding a stationary bike on day one. On day two, they can start non-sport specific light aerobic exercise without resistance training. Day three introduces sport-specific activities without contact, followed by non-contact training drills on day four, which can include a practice setting. On day five, the athlete can engage in full-contact practice. Finally, on day six, they are allowed to return to full competition. If symptoms reappear at any stage, the athlete must rest for 24 hours and then resume the protocol from the last symptom-free step. This policy, when activated, is conservative and values players’ health over anything else. However, this protocol is only activated by a judgment decision an athletic trainer makes while diagnosing an athlete on the field.

Our athletic trainer, Brenna Allen, this school’s sole line of defense for athletes, puts it best: “With concussions, a head injury is very different than just like if you broke your arm; it’s either broken or it’s not broken. With a head injury, it’s not as clear-cut. Concussion signs and symptoms can change and fluctuate, getting better or worse over time.”

Allen’s assessment combines measurable and subjective signs. “I do a neurological assessment as best as I can on the field. That includes cranial nerves, which test reflexes and muscle responses. Then I move to the more objective questions—like, ‘Did you black out? Do you remember what happened just before? Do you have a headache? Do you have neck pain?’”

Allen also collaborates with other trainers, knowing concussion symptoms can be unpredictable. When Allen and I discussed the events that occurred on Oct 2, she said, “The Kennedy trainer texted me and told me everything that happened with you, everything she did, and what she told you, so that if you came in the next day and said, ‘I’m not feeling well,’ I could use that information to see if symptoms worsen. She tells me everything that happened, everything that she did, everything she told you, so that way I have all the information. We collaborate on a lot of things in sports medicine. It is a lot about like, not being like, this is my diagnosis, it’s about what’s best for the athlete. This is how it should be, being open minded, being open to collaboration.”

If my story proves anything, it’s that there’s still work to be done to ensure athletes’ safety. Concussions don’t just heal with time; they can have lasting impacts. And while I might be no stranger to injury, I’m not ready to risk more than I already have.

Student athletes like me deserve a future where our health isn’t left to a rushed five-minute assessment or a single judgment call on the field. Real progress means refining these protocols, ensuring thorough evaluations, and making safety the top priority. Because, in the end, no game is worth sacrificing our future.