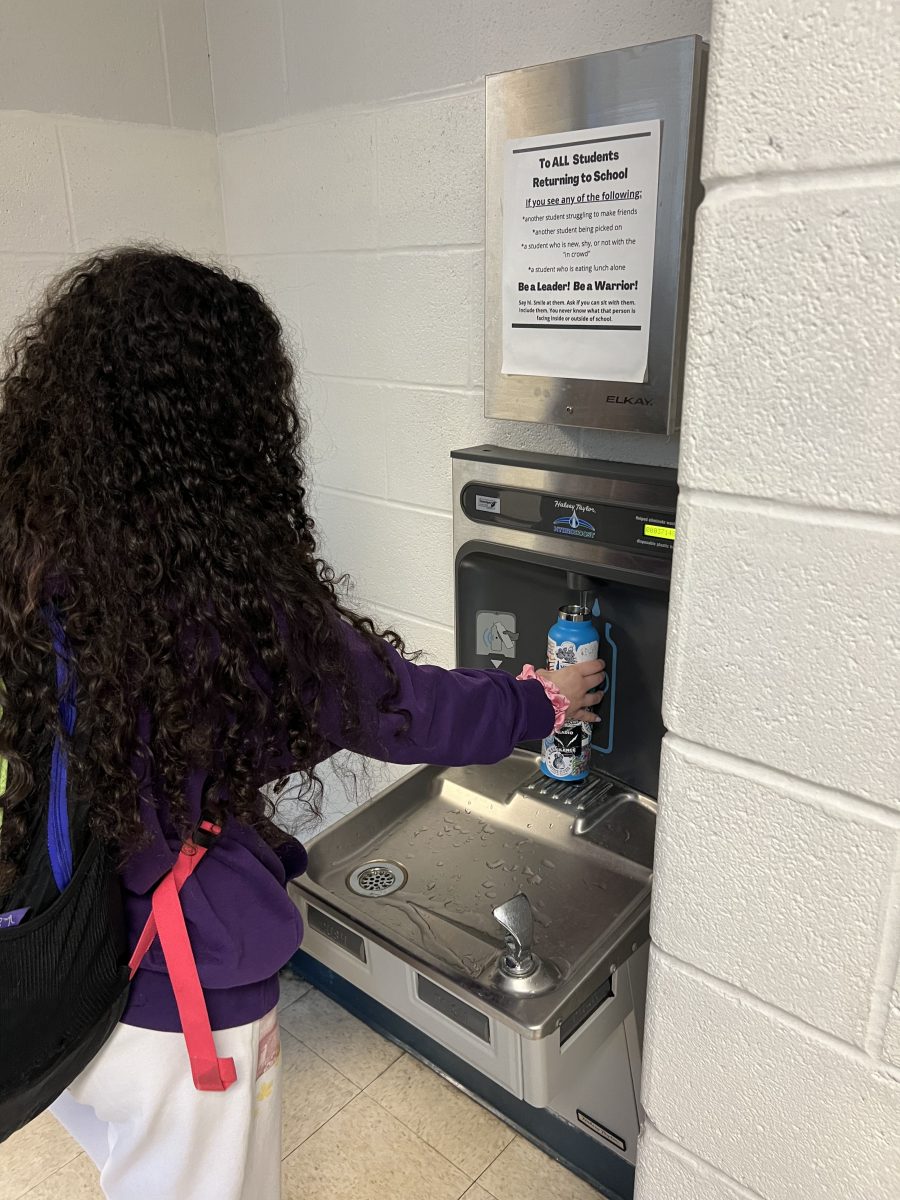

It’s a moment students dread: Their water bottle has run out, but a long school day still lies ahead. Do they choose to refill using the school fountains or do they worry about the water quality here, and wait till they get home? “I don’t really use [the fountains] because I think they are super unsanitary and gross, and the filter is usually always on red, meaning it’s not good water to drink,” junior Yana Kohli said.

In recent years, there have been nationwide efforts to decrease lead and toxin exposure in water. Specifically in 2014, after news broke that residents of Flint, Michigan, had been exposed to toxic and corrosive chemicals in their water, outrage was sparked. In the wake of these events, school systems focused on limiting lead exposure and chemical contamination of their water, a difficult task when considering the plentiful amount of lead pipes and paint in buildings built before the 1980s.

In a 2023 report by Environment America, researchers found that lead in U.S. schools, even in small amounts, can damage learning, growth and behavior. Testing for lead can be difficult due to the highly varying amounts that can often escape showing up in proper tests. “In children, low levels of [lead] exposure have been linked to damage to the central and peripheral nervous system, learning disabilities, shorter stature, impaired hearing, and impaired formation and function of blood cells,” according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The same study gave the state of Maryland a C grade, meaning while there is some level of lead protection in schools, it does not go far enough. In 2021, Maryland passed the Safe School Drinking Water Act. This law focused on requiring schools to fix any drinking fountains that were found to have lead levels above five parts per billion. This law came as a result of lead testing in 2017. Maryland was one of the first states in the country to create lead regulations for schools, and testing ended up revealing contamination in water fountains all over the state. “By requiring testing and remediation and expanding grant funding, Maryland has made big strides to protect our kids from lead in school drinking water. Even at low levels, lead is especially damaging for children’s brains,” director of Maryland Public Interest Research Group (PIRG) Emily Scarr said.

When walking around this school, students likely don’t think twice when going to refill their water bottles or have a sip of water from the fountains throughout the day. However, the clean drinking fountains that students and staff have access to in the school are the result of hard work by the building services staff and MCPS to ensure an absence of lead exposure. This school uses water refilling stations made by Halsey Taylor, a company that supplies many MCPS schools.

According to a representative from Halsey Taylor, the model that we have at our school is nonfiltered with the option to install filtration kits, as well as being able to last for multiple decades if maintained properly.

In order to keep the fountains in safe working conditions, the building service department typically works every day to keep the systems running correctly. “The water fountains do not require a lot on maintenance; if we see something wrong or if it’s not working properly, we put in a work order to the plumbing shop of MCPS. Building service wipes them down daily and runs them each day, we call it flushing, [and] we do that every morning before students enter the building,” building services manager Anthony Murray said.

In regards to filtration, the fountains also are able to indicate when a change is needed. “[The fountains] have a filter, they are changed out when the red light comes on [in a] digital window,” Murray said.

![Editors-in-Chief Ahmed Ibrahim, Helen Manolis, Cameron Cowen, Alex Grainger, Emory Scofield, Hayley Gottesman, Rebekah Buchman and Marley Hoffman create the first print magazine of the year during the October press days. “Only a quarter of the schools in MCPS have programs that are like ours, a thriving, robust program. That makes me really sad. This is not just good for [the student journalists] to be doing this, it’s good for the entire community. What [student journalists] provide to the community is a faith in journalism and that continues for their lifetimes," Starr said.](https://woottoncommonsense.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/wmpoFTZkCPiVA3YXA4tnGoSsZ4KmnKYBIfr18p3l-900x1200.jpg)