A monumental moment for equality in educational and athletic programs came on June 23, 1972, when President Richard M. Nixon signed Title IX of the Civil Rights Act into law. Title IX prohibits discrimination of sex in any educational or federally funded program. This made way for a new wave of girl’s sports in all levels of schools, providing them with the same chances to play and succeed as boy’s teams.

When this school opened in the fall of 1970, the oldest students were the 10th graders who would graduate in 1973. For the school’s first two years of girl’s sports, before Title IX, the teams faced inequality, and lack of recognition, and had to fight for their right to play the sports they played. The rights athletes enjoy now were not available to the school’s first female athletes. Today’s female athletes may not understand how far they have come in the 50 years since Title IX was implemented. Benefitting from the effects of Title IX, as a Wootton soccer alum from 1996-1999, “I never experienced where I didn’t have an opportunity to play,” English teacher Melissa Kaplan said.

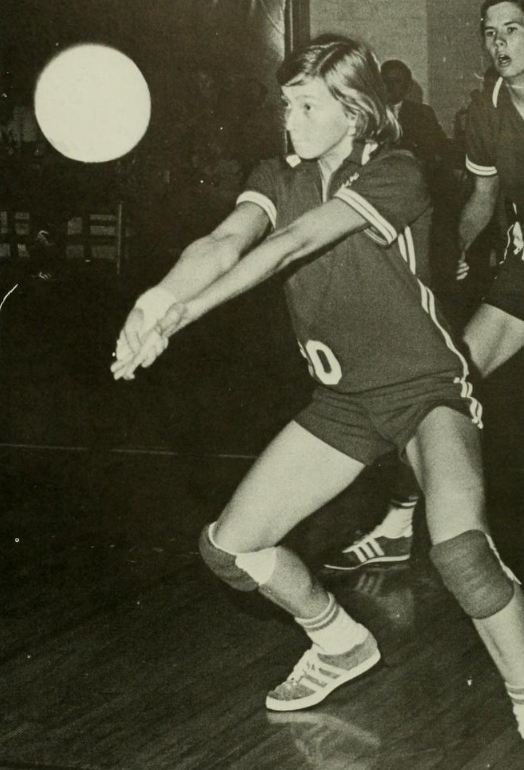

Before Title IX, the boys’ teams were provided funding by the school, but the girls’ teams had to raise money to buy their uniforms and travel to games at their own expense. The girls’ teams also had to yield court and field time to the boys’ teams, sometimes forcing them to practice before the school day began. While boys’ coaches were paid for their work, the girls’ teams were coached by volunteers according to the glass memorial display case. The girls’ teams endured a lack of equality for equipment and they lacked recognition or support. Despite winning athletic championships in swimming, tennis, track & field, field hockey and volleyball, the local press did not cover the accomplishments of these teams, according to a sign in the display case. Additionally, the only opportunities for girls’ state tournaments were in basketball and track at this time.

As difficult as it was for these girls’ teams to persevere and succeed when they had much working against them, they became pioneers of female sports at this school, leading the way for generations to come. Even without a pay incentive, teachers stuck up for these girls’ teams to provide them with the assistance and coaching they deserved. Marion Griffin coached girls’ gymnastics, basketball and track & field. Nina Skavenski and Cheryl Bourgeois coached field hockey, volleyball and softball. Joy Odom coached swimming and Milton Van Winkle coached tennis. Skavenski and Bourgeois led the volleyball and field hockey teams to two county championships. Despite not being paid for all their work and dedication, these coaches stepped up where the school and county failed to provide opportunities to female athletes before Title IX.

Though not given the respect and acknowledgment they deserved by the local press according to the display case, this school’s first female athletes accomplished much, going undefeated, becoming county champions and even state champions in their sports.

After Title IX was introduced into schools, it was still an uphill battle for these first female athletes to make their mark. Emily “Duck” Huntington was a multi-sport captain, Ethel Chambers was a four-sport starter, Heather Dutton was the winning goal scorer in the field hockey county championship, Teresa Harkelroad was a track and swim champion and the girls’ basketball team went undefeated in ‘73 and Page Croyder was the first male or female state champion in track & field in ‘72 and ‘73 at this school. Croyder not only led the way in track & field but she also contributed to the girls’ basketball team and led the volleyball team to multiple county finals. After continuing on to play volleyball at the University of Maryland she became, “a plaintiff in a Title IX complaint against UMD which led the way to greater opportunities for female athletes at the school,” Athletic Director Alton Lightsey said.

Decades after their time at this school, these athletes still aren’t given the respect they deserve for the strides they have made before and after Title IX. In the hall near the upper gymnasium in a glass box stands a trophy now giving long-awaited credit to the girls’ champions from 1970-1973 and pictures of female athletes who took a stand against the inequality they faced.

The school’s female athletes feel there is still inequality, though not in regard to funding. “In terms of attendance and social media presence, there is still work to be done,” senior varsity basketball player Caroline Stasko said.