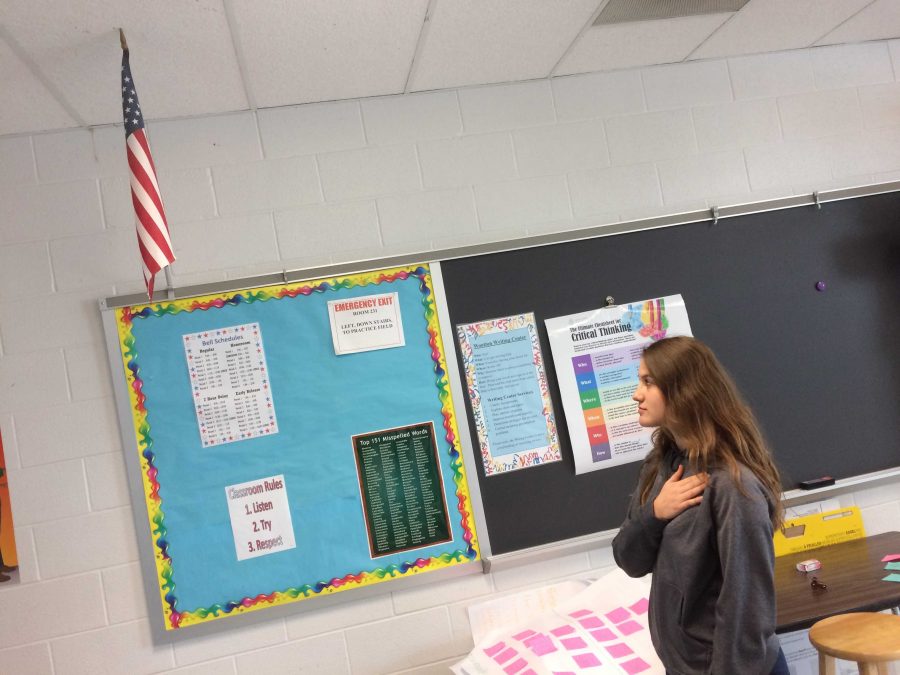

Every morning at exactly 8:30, the announcements ask all students in the school to stand in unison and recite the Pledge of Allegiance. Responses to this prompt, however, vary greatly across the building. Certainly, there are students who stand, with some even putting hand over heart. Yet it is not uncommon to see whole classes of students sitting during this brief (though decades-old) national effort to unify youth behind the flag of the United States.

Americans have a long-ingrained history of patriotism. A study conducted by the World Values Survey from 2000 to 2002 found that approximately 97 percent of U.S. citizens were either “proud” or “very proud” of their country, matched only by Poland and beat only by Egypt’s 98 percent. And while American patriotism may have declined since the study was conducted, particularly as the time since the September 11 attacks has increased, the Pledge of Allegiance remains one long-lasting example of the unique element of American patriotism that does not exist in most nations around the world.

Debate over the Pledge typically falls under one of two categories. The first is that it excessively promotes nationalism among the youth of the United States by heavily emphasizing its importance. Advocates of this idea tend to believe that it should be up to the citizen to individually decide whether or not to harbor patriotic feelings rather than having the government seemingly shove such feelings down one’s throat.

The other debate centers mostly upon the use of ceremonial deism through the use of the words “under God.” People opposed to this phrase see it as violating the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause by officially advocating in favor of faith in a nation where church and state are supposed to be markedly separate.

To learn more about students’ perspectives on these topics, a survey was conducted throughout lunch, featuring the perspectives of 103 students. Its results will be explored in depth later, as first it must be understood how and why the Pledge of Allegiance came to be so prevalent in the American education system.

A History

George Balch, who fought during the Mexican-American War and later the American Civil War, originally composed the Pledge in 1887. It differs greatly from the current one in many ways, most notably being in its advocation for “one language” behind which our nation stands. Balch’s goal was to educate Americans (especially immigrants) about the greatness of American values, hoping to use the pledge as a way to shed any previous loyalties.

Francis Bellamy, a Christian socialist minister, revised Balch’s pledge and crafted his own, eliminating the reference to God while still underscoring the beauty of American republicanism, liberty and justice. It became widely adopted when President Benjamin Harrison invited Americans to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ landing in the New World, and, as such, the National Education Association began using it in schools in 1892. Since then, it has maintained its role in public schools.

The Pledge was briefly refined in 1923 and was formally adopted by Congress in 1942, but it underwent its most significant change in 1954, when Congress amended the flag code (the military guidelines regulating proper flag use) to include the words “under God” in the pledge as a measure to counteract Soviet atheism. President Dwight D. Eisenhower said that the addition reaffirmed “the transcendence of religious faith in America’s heritage and future.” Since then, schools across the nation have been required to recite it daily.

Unnecessary Nationalism?

The 1943 Supreme Court verdict in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnett officially declared that all students have the right to refuse to say the Pledge of Allegiance if they desire. As such, no teacher can force a student to stand in the morning, no matter how strongly it is encouraged.

Nonetheless, advocates of freedom of speech feel as though younger students in particular are forced into reciting it on a daily basis. In Montgomery County Public Schools, elementary students are not clearly given the option of whether or not to stand, though it is always present. Students are typically told simply to “please stand for the Pledge of Allegiance.”

Implied in this is the constitutional right to remain seated. Yet such young students are simply not often aware of the choice, and as such often recite the patriotic oath without truly comprehending what it means. A sense of nationalism is thus baked into young children, teaching them a respect for their country and its republic from an early age.

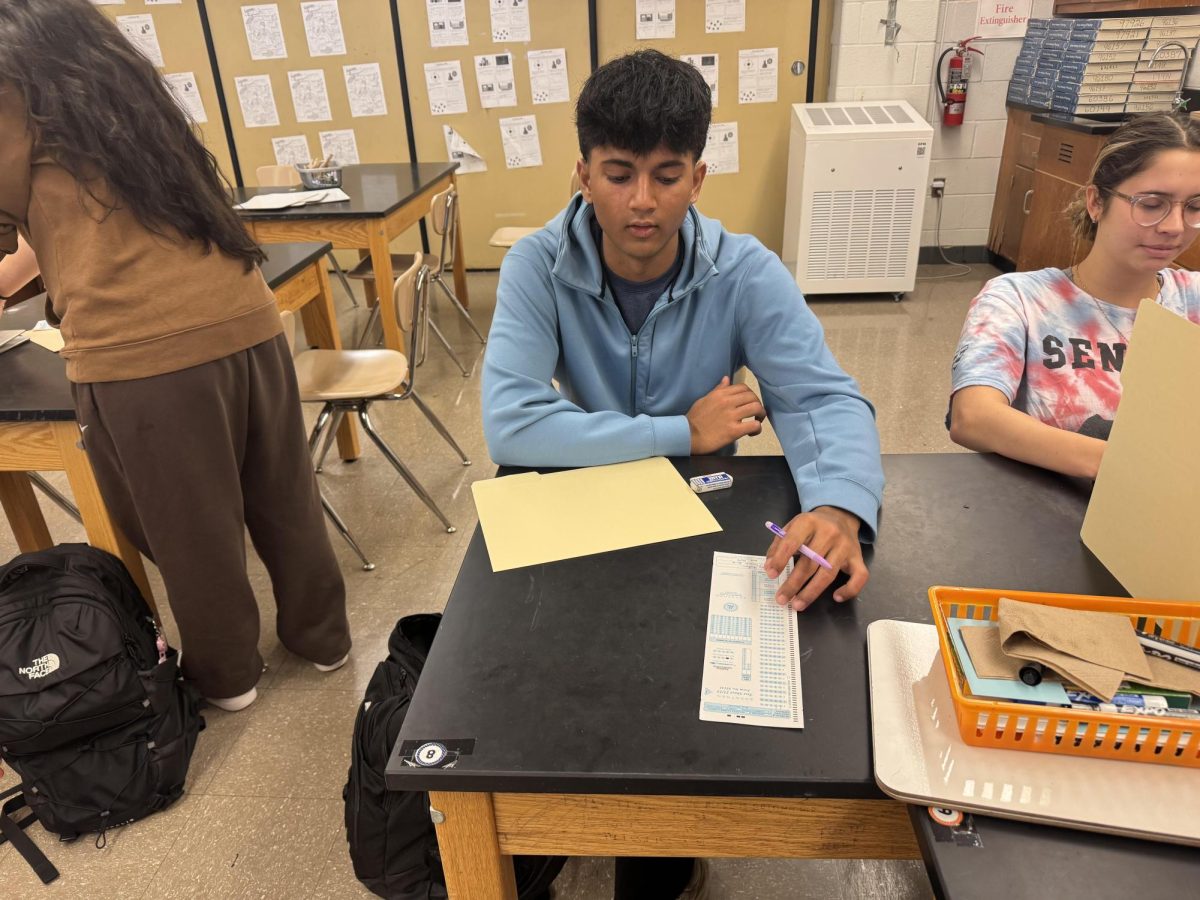

Opinions on the Pledge of Allegiance here are mixed. The aforementioned survey found that 50.5 percent of students stood for the pledge “sometimes,” while 31.1 percent stood “every day” and 18.4 percent “never” stood. If students at the extremes are thought to be the most opinionated relative to their level of patriotism, it makes sense that a minority of them hold a strong stance either in favor or against it. The majority of students, however, are less inclined to have a hardline stance on the pledge. These tend to be students do not believe it should be removed from school, but also aren’t students who feel it is their duty as citizens to stand.

Is this what John McCain was referring to when he warned against “half-baked nationalism” in today’s society? Perhaps so. Or perhaps students simply do not feel as pressured into participating as they did when they were children.

As students grow older, they grow more aware of their rights, their own opinions, and what they (literally) are willing to stand for. It makes sense that there would be more resistance to such an effort from students in high school rather than in elementary school, when the pledge was simply part of the daily routine.

Likewise, teachers’ policies vary from class to class. During my four years here, I have had five different teachers for first period (during which time the morning announcements are shown), and the policies implemented with respect to the pledge vary greatly. Some teachers firmly express their belief that students should stand for the pledge, nagging them to “be respectful” or to “be quiet” during the pledge (teachers cannot in fact make you be quiet during the pledge either, though this is more a matter of respect). In those environments, far more students will stand than in a class where a teacher makes no reference to the pledge or lets students talk through the announcements. In those classrooms, it is not uncommon for only two or three people to stand.

The fact that students are so impressionable when it comes to the pledge reveals that a large portion of students (comparable to the “sometimes” portion of our survey) aren’t particularly patriotic. Whether or not the pledge actually does its job, then, of instilling patriotic values is up for debate.

No Nation under God

The controversial addition of the words “under God” in 1954 to demonstrate America’s commitment to the importance of free faith arguably had a reverse effect. In professing the country’s love for God, it ignored those who openly refuse to acknowledge a monotheistic existence. In 2015, the Pew Research Center found that 22.8 percent of the nation was unaffiliated with any religion or deity.

Thomas Jefferson (who himself coined the phrase “separation of church and state” in 1802) remained firmly committed to this principle. The First Amendment does not explicitly prohibit the government from referencing God, but it does prohibit them from promoting or supporting an established religion. Technically, referencing a God without proclaiming from which faith one would belong has not yet been defined as unconstitutional. It is the reason the addition to the pledge was allowed at all and why “In God We trust” became the U.S.’ official motto in 1956, replacing the Latin E pluribus unum.

So while so far it is legally permitted, that does not answer whether or not it is offensive. Part of the survey we conducted also asked students their opinions on whether or not “under God” should be removed from the pledge. A minority of those polled (37 percent) responded “yes” to its removal, while 63 percent believed it should remain.

The words are obviously more likely to offend those who are directly affected by it. This school remains a community with many students who are actively involved in religious organizations, such as church groups and BBYO. A reference to a nonspecific God allows for a broader appeal among the public, even if it is not universally supported.

The First Amendment protects one’s right to refuse to speak any part of the pledge. Those who protest the pledge due to its acknowledgement of a God may choose to ignore any part of it they wish. Nonetheless, passions run expectedly high when it comes to religion and government in a country with such a large Christian population (70.6 percent in 2015).

Conclusion

Whether or not the Pledge achieves its goal or is inherently offensive cannot be measured simply by results from a poll at one (remarkably rich, left-leaning, racially askew) school. But it can be measured in the coming years as the children of the 2000s grow into full-fledged adults. Whether or not a decline in patriotism occurs in the next few decades, it must, to some extent, be due to the reactions of the government fostering support from such a young age.

Matthew Klein

Managing Editor