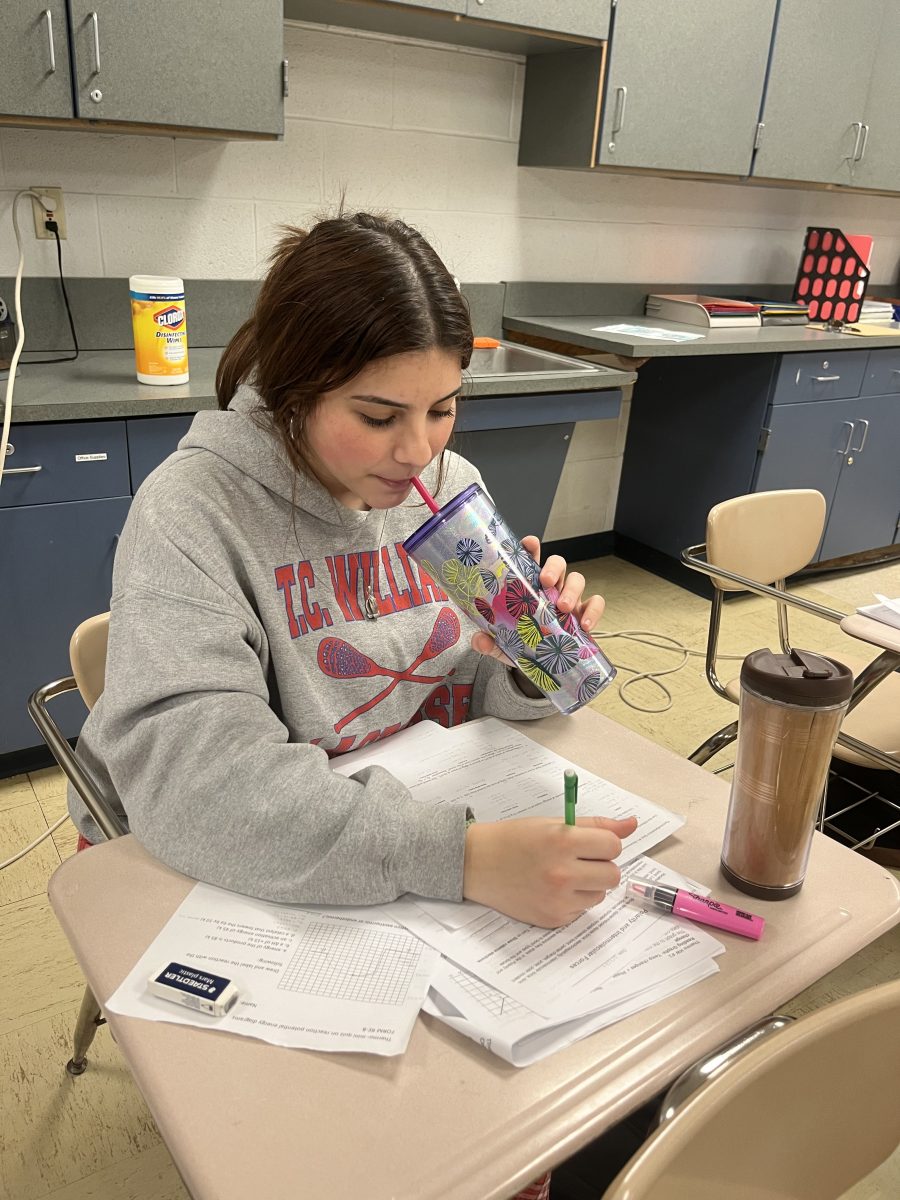

Coffee and other caffeinated drinks have become increasingly popular, especially among adolescents. With this upswing, concerns about its effects have arisen.

Caffeine is a psychoactive drug with similar properties to cocaine and amphetamine. NIH defines caffeine as “a naturally occurring central nervous system (CNS) stimulant of the methylxanthine class and is the most widely taken psychoactive stimulant globally.”

Caffeine is naturally found in the leaves, seeds, and nuts of certain plants. It’s commonly consumed in coffee, tea, soda, and energy drinks and is available in capsule form over the counter. Caffeine can be beneficial, increasing alertness and decreasing fatigue. Studies suggest that it boosts cognitive performance. In low doses, it can be part of a healthy diet linked to increased metabolism and improved exercise.

However, excessive caffeine intake can be toxic, varying from person to person. According to Johns Hopkins, “too much caffeine can cause issues such as increased anxiety, increased heart rate and blood pressure, acid reflux and sleep disturbance.”

These dose-response effects can be more critical on adolescents due to their smaller, developing bodies. While the FDA hasn’t set limits on caffeine intake in children, Health Canada recommends “a maximum daily caffeine intake of 2.5 mg per kilogram of body weight (mg/kg bw) for children under 12 years.”

Specialty coffee drinks targeted toward children include high amounts of sugar and cream. A health article from Johns Hopkins University discusses these drinks and their impact on kids. “They’re more like desserts and can contribute to excess sugar and calorie consumption if consumed often,” Johns Hopkins said.

Habitual caffeine consumers can find their bodies relying on caffeine, often leading to withdrawal symptoms. Common symptoms include anxiety, headaches and nausea. Cutting back on caffeine slowly over time can help reduce symptoms. According to the Journal of Caffeine Research, “studies suggest that dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens shell may be a specific neuropharmacological mechanism underlying the addictive potential of caffeine.”

Due to the general population being caffeine consumers without problems, The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) created restrictive diagnostics to avoid overdiagnosis. According to the DSM-5, over 250mg of caffeine consumption can lead to caffeine intoxication.

Despite its addicting effects, it is freely available and sold unregulated. “Caffeine is similar to most other drugs that are reinforcing, which caffeine is. People desire the effect and repeat the behavior over and over again. When reinforcers like that are easily accessible and inexpensive, their use may get out of control,” Alan Budney, Ph.D., professor of psychiatry at Dartmouth Medical School, said.

Experts say that adolescents should avoid habitual caffeine consumption and take it in moderation as needed. The risks and toxicity increase with highly caffeinated energy drinks becoming more widely consumed, often containing other harmful or artificial ingredients.

Children relying on caffeine should meet with their pediatrician to understand the reason for their fatigue and discuss healthier alternatives.

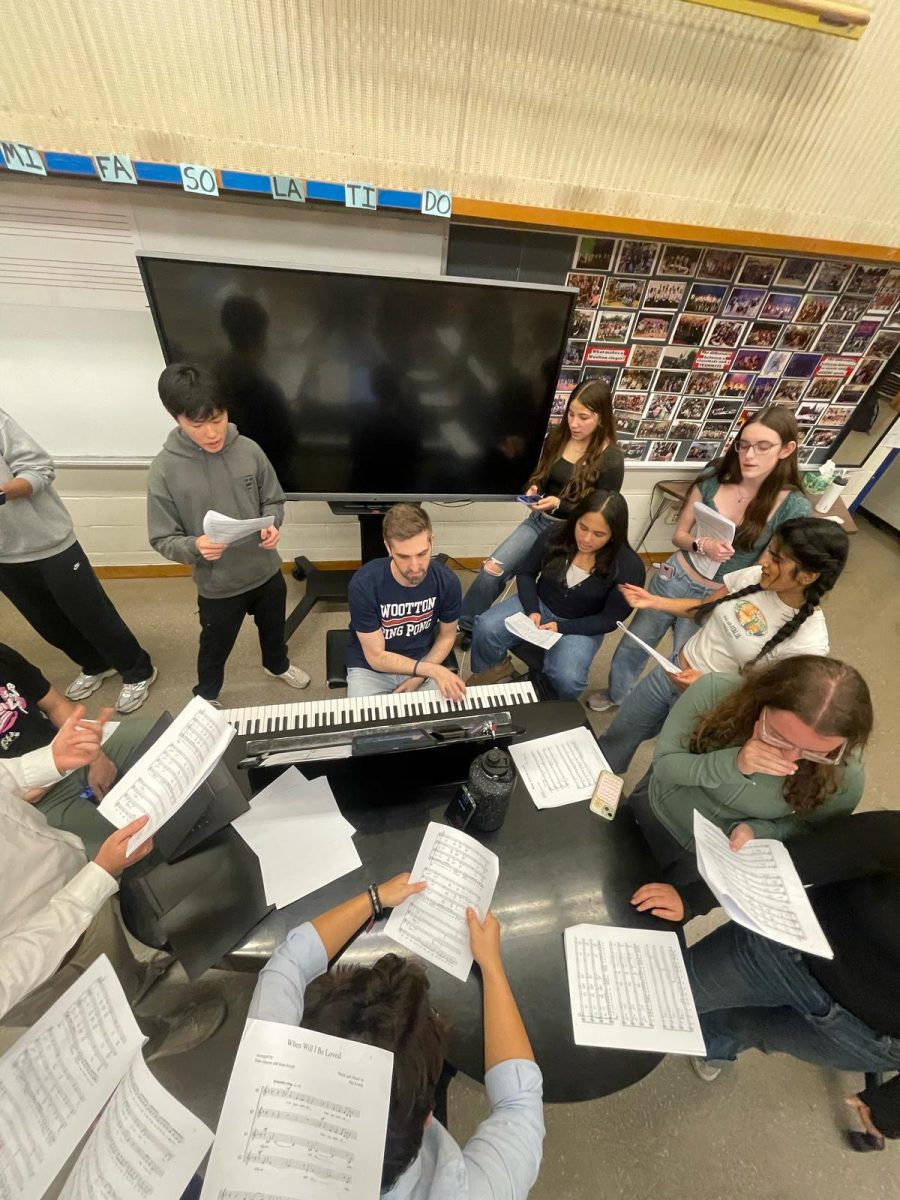

![The 2025-2026 Editorial Board Alex Grainger, Cameron Cowen, Helen Manolis, Emory Scofield, Ahmed Ibrahim, Rebekah Buchman, Marley Hoffman, Hayley Gottesman, Pragna Pothakamuri and Natalie Pak (Chase Dolan not pictured) respond to the new MCPS grading policy. “When something that used to be easy suddenly becomes harder, it can turn [students’] mindset negative, whereas making something easier usually has a better impact. I think that’s where a lot of the pushback comes from. But if you put emotions aside, I do think this change could help build stronger work ethic,” Ibrahim said.](https://woottoncommonsense.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/fqr5bskTXpn0LRQMmKErLuNKdQYBlL726cFXBaWF-1200x900.jpg)