Gun violence, along with apple pie and baseball, has become a staple in American society. It’s everywhere; horrifically intertwined with practically every news story and clutching dangerously onto the minds of families of victims. It serves as an agonizing reminder of what they have lost, yet it’s unable to produce even a shred of empathy from the public.

Is this not the painful truth? How many times do we see news stations report another mass shooting and truly mourn for the murder of the innocent? How many times do we really feel grief and outrage at the horribly tragic situation being presented in front of our very eyes? The unfortunate answer is rarely, if ever. Maybe we do for a moment, for just a fleeting moment, when you see a gut-wrenching video of a sobbing mother desperately crying out for her child. Or maybe when the pictures and names of victims of a school shooting are presented onscreen you realize with a drop in your stomach that the victims couldn’t be older than seven or eight. But that’s all it is: fleeting, brief, only a passing thought before we move on with our lives and forget about the entire ordeal.

The main cause of this lack of compassion has to do with the sheer number of tragedies that occur every day. With the amount of violent crimes news stations have to cover, each story ends up receiving a negligent amount of news coverage. We watch a three-minute story on a mass shooting, we potentially feel a spark of empathy, then the news drags our attention to something else, our eyes and minds follow, and we move on; this cycle repeats itself over and over again, leading to normalization of violence across the nation.

This small amount of media coverage for each incident means that we can’t fully empathize with one incident before turning our attention to another, so what our brains do to prevent us from stretching our emotional attention too thin is desensitizing ourselves. According to Professor Bruce Harry of the University of Missouri School of Medicine, we become psychologically numb when exposed to a plethora of trauma and violence; it’s a defense mechanism that all of us have, as our brains will try to create cognitive and emotional distance in order to keep us mentally healthy.

However, desensitization isn’t an inherently negative quality. In certain instances, it can be useful; without desensitization, medical students wouldn’t be able to study cadavers, and firemen wouldn’t be able to continuously save people with charred body parts and melting faces. The information and services derived from these two examples alone have extremely significant importance for the medical community and for first responders. Additionally, desensitization can be used to help people cope with phobias and anxiety, as stated in an article published to NIH by doctor Greg Dubord. By gradually exposing patients to their fears in stages, the goal of the process, which is called systematic desensitization therapy, is to teach patients relaxation techniques and slowly desensitize them to their fears. While this process can be used for more “mild” fears, such as arachnophobia, it can also be used for severe disorders, such as PTSD, that significantly and negatively affect a person’s everyday life.

Yet there are always two sides to every coin, and when it comes to gun violence specifically, desensitization is detrimental to the bigger picture. Desensitization does not help alleviate the crimes around us, nor does it make us truly safer; rather, our lack of interest stands as an obstacle that hinders resolution. Seeing incidents as not just headlines, but instead as human stories that are filled with human emotion and human suffering, personalizing these tragedies to empathize with the victims and acting upon this empathy to promote change are the only ways this vicious cycle of death and despair that is being perpetuated by our apathy will be prevented from continuing further.

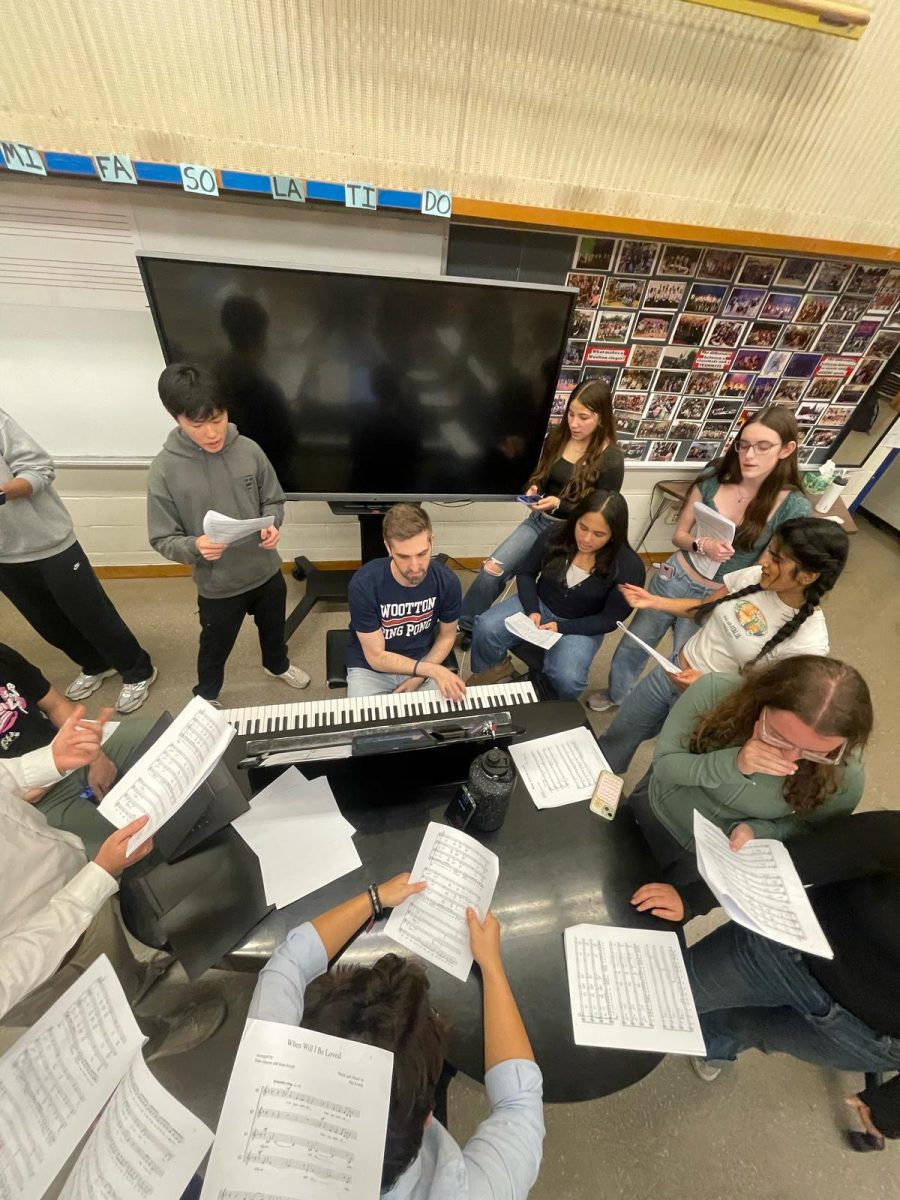

![The 2025-2026 Editorial Board Alex Grainger, Cameron Cowen, Helen Manolis, Emory Scofield, Ahmed Ibrahim, Rebekah Buchman, Marley Hoffman, Hayley Gottesman, Pragna Pothakamuri and Natalie Pak (Chase Dolan not pictured) respond to the new MCPS grading policy. “When something that used to be easy suddenly becomes harder, it can turn [students’] mindset negative, whereas making something easier usually has a better impact. I think that’s where a lot of the pushback comes from. But if you put emotions aside, I do think this change could help build stronger work ethic,” Ibrahim said.](https://woottoncommonsense.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/fqr5bskTXpn0LRQMmKErLuNKdQYBlL726cFXBaWF-1200x900.jpg)