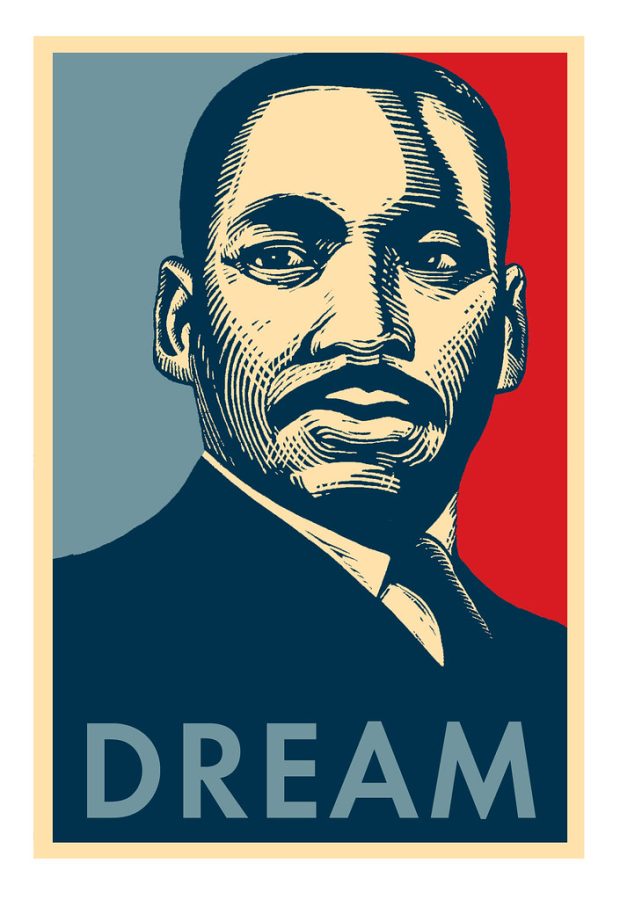

Martin Luther King’s forgotten dreams

Image by Giltronix used with permission from Google Commons

While his legacy as a civil rights activist is well-known, Martin Luther King fought for far more than the dream we remember.

Martin Luther King Jr. was one of the most inspiring and effective Civil Rights leaders in American history, but he fought for far more than Civil Rights. King forcefully criticized the government for their handling of the Vietnam War, becoming one of the first Civil Rights leaders to do so. In the months before his assassination, he had moved his sights to economic justice, and was organizing a Poor People’s Campaign in an effort to secure a bold shift in America’s treatment of the impoverished.

As another Martin Luther King Day passes, it is worth remembering the full breadth of his advocacy and ideas, insteading of boiling down decades of organizing, protest and advocacy to one phrase, from one speech.

Economic Justice

The Civil Rights movement achieved legislative success throughout the 1960s, and King among other leaders began to focus on a new, but just as crucial cause to fight for: economic justice. King is remembered mostly for his speech at the March on Washington, but that legendary protest’s full name was The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

According to the The King Institute, on Feb. 1, 1968, Memphis garbage collectors Echol Cole and Robert Walker were crushed to death by a malfunctioning truck. Eleven days later, frustrated by the city’s response to the latest event in a long pattern of neglect and abuse of its Black employees, 1,300 men from the Memphis Department of Public Works went on strike. Sanitation workers demanded recognition of their union, better safety standards and a decent wage.

This would be King’s last work of protest before his assassination. While showing support for the workers at a rally in March 1968, King said, “You are reminding the nation that it is a crime for people to live in this rich nation and receive starvation wages … working on a full-time basis and a full-time job getting part-time income.”

King’s words reflect on our present society, as we are still far away from his dream of economic justice. Although America has a ways to go in both respects, it can be argued that since King’s assassinaton, more progress has been made toward racial equality than creating a more economically just economy.

The federal minimum wage in 1968 was $1.60 an hour, a source of protest. That number that is deemed reprehensible, when adjusted for inflation, is over $5 higher than the current federal minimum wage.

Economic inequality persists today and has in many ways worsened. According to the The Rockefeller Foundation, Black–white family income disparities in the United States remain almost exactly what they were in 1968. Additionally, Black home ownership, a sign of the racial wealth gap, stands at about 40.6%, compared with 73.1%for whites.

The top 1% has flourished in the decades since King’s death, and according to Bloomberg, now holds more wealth than the entire middle class, defined as the middle 60% of the country. In a 1961 speech to the Negro American Labor Council, King said, “Call it democracy, or call it democratic socialism, but there must be a better distribution of wealth within this country for all God’s children.”

In his time, King recognized the challenge of going beyond racial progress and attempting to change an economy for the better. In a 1967 speech titled “The Other America,” King said, “We must see that the struggle today is much more difficult. It’s more difficult today because we are struggling now for genuine equality. It’s much easier to integrate a lunch counter than it is to guarantee a livable income and a good solid job. It’s much easier to guarantee the right to vote than it is to guarantee the right to live in sanitary, decent housing conditions. It is much easier to integrate a public park than it is to make genuine, quality, integrated education a reality. And so today we are struggling for something which says we demand genuine equality.”

The Poor People’s Campaign

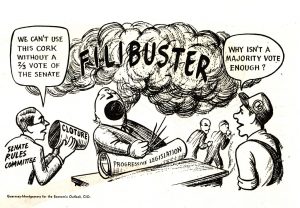

The Poor People’s Campaign was created by King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. According to history.com, rather than holding a one-day demonstration to raise awareness about income inequality, leaders of the Poor People’s Campaign called on activists to camp out on the National Mall until the federal government committed to the anti-poverty policies featured in their economic bill of rights.

Among the policies in this economic bill of rights was the federal government’s prioritization of helping the poor through a $30 billion anti-poverty package, which included a commitment to full employment (essentially a zero percent unemployment rate), a guaranteed annual income measure, and more low-income housing.

This campaign could have been the crowning achievement of years and years of strikes and protests in support of the poor. It could have led to massive policy shifts and made poverty the most important issue of the 1968 presidential race. Tragically, The Poor People’s Campaign fizzled out after King’s death.

Vietnam

It is hard to imagine now, but King attacking the government over the Vietnam War was groundbreaking, not only for who he was criticizing, but his status as a Civil Rights leader led to people thinking he should “stick to” that topic. However, King famously said in his letter from a Birmingham Jail that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” He could no longer stay silent about the Vietnam War.

King’s 1967 speech “Beyond Vietnam” has been forgotten by history, but it is perhaps even more relevant than his 1963 “I have a dream” speech. By this time there were over 500,000 American soldiers fighting in this war, and more than 58,000 would die throughout the conflict. During the Vietnam War, there were more explosives targeted at Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos than were dropped on all of Europe during World War II.

In this powerful address, one of the reasons King forcefully opposed the war was that “we are taking the Black young men who had been crippled by our society and sending them 8,000 miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in southwest Georgia and East Harlem.”

As the 1960s continued, rioting was an increasingly significant issue for peaceful protestors like King who viewed nonviolent action as the best way to enact change. But when addressing Vietnam, King showed empathy toward rioters’ frustration, saying “But they ask — and rightly so — what about Vietnam? They ask if our own nation wasn’t using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, to bring about the changes it wanted. Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today — my own government.”

King’s work for racial equality was incredible, and if not for an assassin’s bullet, his work for economic equality had the chance to eclipse it. It is not that the King’s Civil Rights advocacy should be forgotten. The problem comes when that is all we are taught is his Civil Rights work. King wasn’t a one-dimensional leader and history should not reduce him to one. He should be remembered as a giant who fought for the voiceless, and was unafraid to fight against injustice, wherever it could be found.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Thomas S. Wootton High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Ethan is a 2023 graduate.