Every year my elementary school had a Chinese New Year celebration put on by the second grade class. It was the typical school celebration; make decorations, walk in a parade and sing songs that we had been practicing for nearly a month.

One of those songs repeated the Chinese phrase “gong xi fa cai” (happy lunar new year) over and over. Being the immature second graders that we were, we got bored with the constant practice and began to goof off. One student, who was Asian, decided it would be funny to switch around the words of the song and turn gong xi fa cai into gong hey fat choy. (Both pronunciations are correct, depending on which Chinese dialect you are speaking.) The teacher gave him a bit of a scolding look but didn’t say anything. A moment later, his friend, who was white, repeated the words and the teacher completely blew up at him, yelling about disrespecting other cultures.

At the time, I just didn’t get it. Why was my teacher upset at the white kid but not the Asian kid who said the exact same thing? But as I got older, I saw that this was something that happened often; someone could say one thing but someone else couldn’t say the exact same words. Someone who is gay can make fun of himself for being gay, an Asian can say that they have squinty eyes, a blonde girl can say she’s such a white girl, and each time, no one really thinks anything of it. But when someone who is straight teases his gay friend, when a white person comments on an Asian’s glasses, when an African American calls the blond a white girl, everyone is suddenly furious. And this doesn’t just apply to comments about race and culture, it can apply to any group. But why does it happen? Why can I insult my own culture, but you can’t?

In- and out- groups

Remember middle school? Frost and Cabin John? You probably do, even though you wish you didn’t. Middle school was that awkward phase where the majority of us had braces and a bad sense of style. Looking back at it a lot of us think “how did we go from that awkward, gawky, nerdy person to who I am now?”

The answer is that we got older and our views of what was cool changed. We went through different experiences and formed different opinions. Our likes and dislikes changed and our views of the world changed. In short, we grew up. As we grew up, and into ourselves, we also grew into our social groups.

Now, think about your group of friends. What do you have in common with them? Are you all the same ethnicity? Do you all participate in the same activities? Do you take the same classes?

We naturally divide ourselves into a group with people who are similar to us, as our friends are, and anyone who isn’t similar probably isn’t purposely excluded from the group, but they don’t fit in either.

According to Psychology Today, those who “share our particular qualities are our ‘in-group’, and those who do not are our ‘out-group’.”

Some in-groups are based on our likes and dislikes. For instance, being on a sports team automatically makes you a part of that in-group, but others are determined when we are born: sex, race, age, family, etc.

Like everything else, in-groups affect our lives more than we realize. They impact the way we think about others and the way we interact with each other. After all, most people act differently with their friends than they do with their teachers.

Insults within the in-group

Have you ever insulted your sibling? You probably have. It’s something we all do. Your little sister does something that you hate and you complain to your friends about it and probably say a few unflattering things about her. It’s normal.

But have you ever insulted your friend’s sibling? Has your friend ever insulted your sibling? Well, if they did, you’d probably be furious. You’d probably think something along the lines of: “How on earth did they think they had the right to say that? How in the world did they think it was an acceptable thing to say?”

Well, what if your friend said the exact same thing about their sibling? If they had insulted their brother instead of yours, you wouldn’t care. You wouldn’t give it a second thought. But why does it matter if they made that comment about their brother or yours?

Your family is an in-group that you are a part of from birth, and there are different standards of what’s acceptable behavior for people within the in-group versus people who are outside of the in-group, one of them being that you can insult the in-group you are a part of.

“It’s like self-deprecation,” sociology and psychology teacher Amy Buckingham said. “By identifying yourself as part of the in-group, you’re taking on that group’s identity and just like how you can insult yourself, you can insult your group too. We do this to elevate our own status. We always want to think we are superior to others, including the group we are a part of. By insulting our own group we are both identifying ourselves as a part of that group but also putting the group down in comparison. It’s like how bullies will pick on someone weaker to make themselves feel better.”

Bias and discrimination

Back to middle school. Remember how there were always the kids who were, for lack of a better phrase, the “cool kids”? Even if this wasn’t your middle school experience, I’m sure you’ve seen a movie that’s got the division of cool kids and nerds. Well, if we think of all of in-groups and out-groups as a bunch of teenagers, the cool kids are the in-group and everyone else is a part of the out-group.

Obviously, or at least according to Hollywood, the cool kids think that they are better than the nerds. This is also true of in-groups and out-groups. The people who are a part of the in-group, whatever that in-group may be, are biased toward themselves and they favor themselves over anyone else.

The bias towards the in-group you’re a part of, appropriately called the in-group bias, is not because the people who belong to the in-group dislike those who are a part of the out-group, but because all their positive feelings of trust, sympathy, understanding, admiration, etc. are directed toward the in-group. While it may sound bad that the out-group doesn’t receive these feelings too, think about it. Don’t you trust your friends more than the random kid who sits next to you in math?

Stereotypes and how to break them

“The diversity at Wootton is definitely there,” senior Ethan Kim said. “But that does not exactly mean that it is easy to make friends from different racial groups. It you look around, the Asians usually stick with other Asians, and white people usually stick with other white people. This isn’t racism. It’s just being more comfortable with people who literally have the same color skin.”

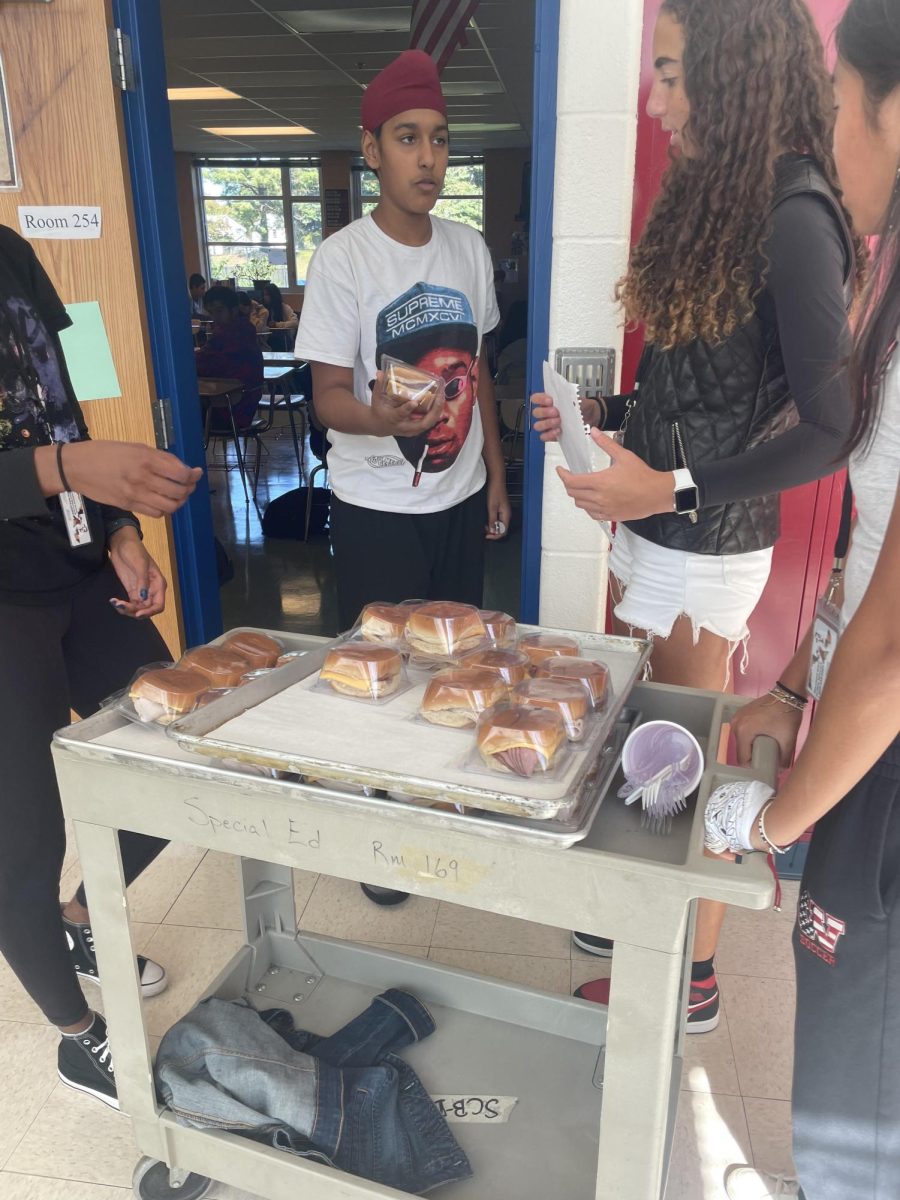

The truth of Kim’s statement can be seen if you walk around the school at lunch. There are lots of different ethnicities, but very few lunch groups of mixed ethnicity.

While it can be good to stick with other people who are like us, as there is safety in numbers, that also makes it harder to break stereotypes. For example, if you’re Asian and you hang out with mostly other Asians, white people won’t be able to get to know you. If they can’t get to know you, then it’s harder to prove that you don’t conform to the Asian stereotype and therefore the stereotype is wrong.

This is where it can be helpful to have a person who is a part of multiple, conflicting in-groups- in the case of this example, a biracial kid who can go back and forth between the two groups creating a “bridge” between them and making it easier for them to intermingle and get to know each other.

Recently, many of us have been upset with current events and we protest the best we can by going to marches and demonstrations in D.C.. We speak out in any way we can in order to combat stereotypes, racism and double standards, to get rid of the discrimination and derogatory terms. We fight for the rights that we all deserve and we try to make the idea of equality a reality.

But how can we expect to get equal treatment when our interactions and ideals of what is acceptable for different groups prove that we obviously don’t hold each other to equal standards?

Shelby Ting

Front Page Editor